Stuck on 7th chords?

This article will teach you everything you need to know about 7th chords, including:

- The 7th chord formula

- The basic types of 7th chords most commonly found in jazz

- Unique sounding, rarer 7th chord qualities

- What are chord extensions, and how to use them

- Actionable tips for reading chord charts on the gig

- Plus, we’ll provide some essential listening recommendations along the way!

Also, we’ll provide basic chord charts for piano and guitar so as to not leave any chord player out! This ultimate guide to 7th chords will give you everything you need to know to understand 7th chords in theory and on the gig.

If you want to learn how to play 7th chords like a pro and become the best jazz musician you can be, then you should check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

We have over 10 years of incredible jazz education resources, including masterclasses, in-depth jazz standard studies, and even specialized Instrument Accelerator Courses to help you master jazz on your specific instrument.

Become the player you want to be. Check out the Inner Circle.

Table of Contents

7th Chords In Music

Though present in pop music today and certainly present in jazz, it took the musical world a bit of time to warm up to the sound of 7th chords.

If you look hard enough, you can find examples of incidental 7th chords as far back as Renaissance music, but they were pretty uncommon up until a century and a half ago.

Today, 7th chords are the basic building blocks of jazz harmony and are regularly found in modern music.

To speak the language of jazz and perform jazz with other musicians, you’ll need to understand how 7th chords work, how you can play them (or over them), and how to comprehend them on a chord chart. We’ll first go over 7th chord fundamentals and then move on to more complex 7th chords.

Use the Table of Contents to skip to later sections if you don’t need a 7th chord review!

Understanding the 7th Chord Formula: Triad + the Seventh Scale Degree

Let’s start with the basics—understanding the 7th chord formula.

Major and minor triads are the basic harmonic building blocks in Western music. You build a triad by choosing a root note from a particular scale and stacking thirds on it using the scale degrees from that scale.

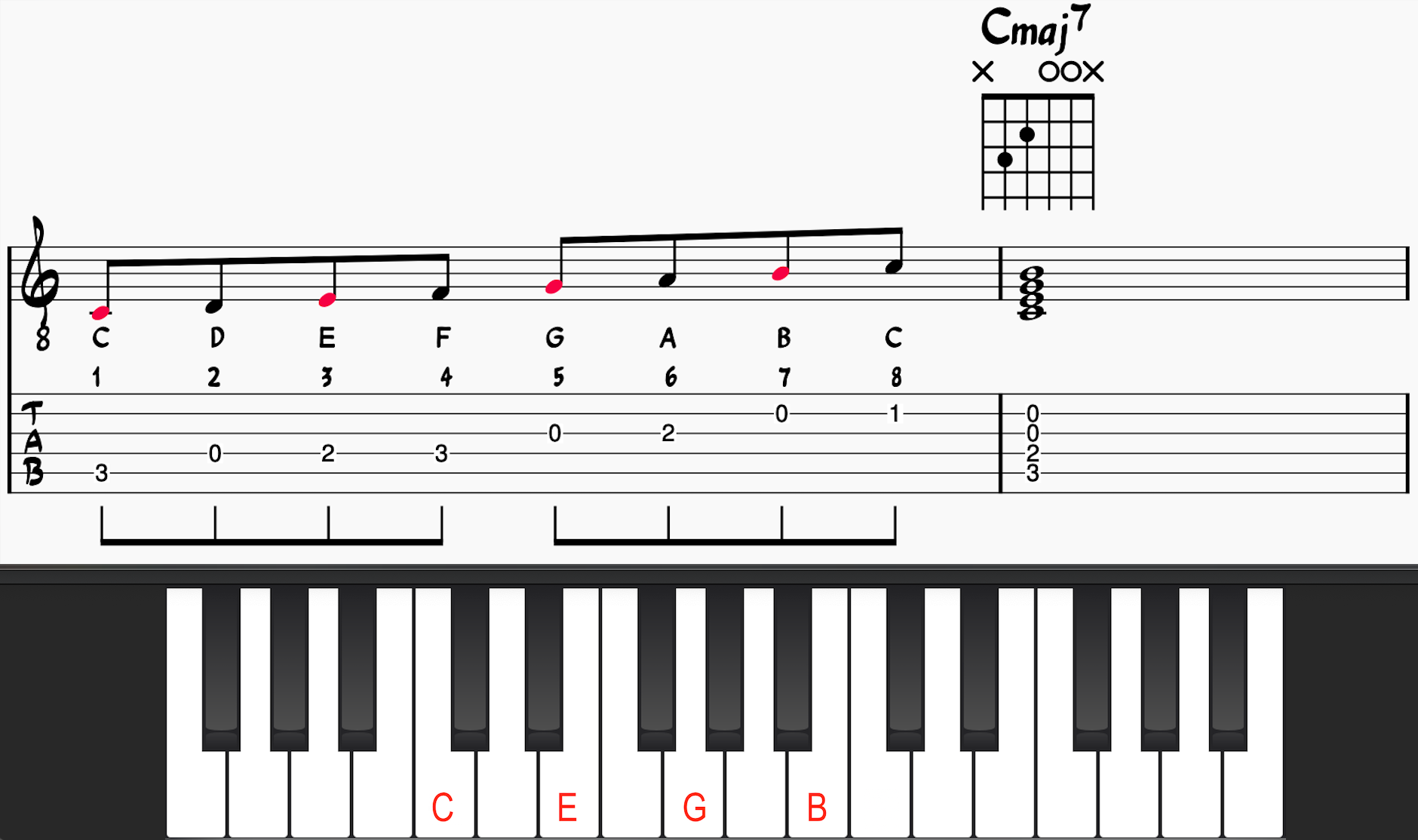

Using the C major scale as an example, a C major triad would be spelled C-E-G:

- C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C

Though 7th chords definitely have their place in popular music today, most popular music still uses basic triads.

Seventh chords are built on the same principle. However, the difference between triads and 7th chords is that 7th chords have an additional note added to the mix—we stack another third on top of the fifth note. This gives us four note chords.

In the case of a C triad, we add one more 3rd to the sequence to get a Cmaj7 chord:

- C-D-E-F-G-A-B-C

You can think of the 7th chord formula as [R + 3 + 5 + 7] or [C + E + G + B] in the example above.

That’s it!

Here is a diagram showing the C major scale and the Cmaj7 chord you can build by playing the Rt. 3rd, 5th, and 7th:

We’ll use this formula to build all five basic types of 7th chords in jazz harmony. We’ll start with basic triads—like [C-E-G]—and add the appropriate type of note to arrive at our 7th chord: [C-E-G-B].

If you want more on jazz guitar chords, including more voicings and chord inversions, check out these 20 jazz guitar chords you need to know! For pianists, check out our 15 must-know jazz piano chords.

What Are The Five Basic Types of 7th Chords Found In Jazz Harmony?

A chord’s quality is determined by its component intervals’ relationship to the chord’s root. (By component intervals, I mean the different relationships between each note in the chord and the chord’s root note.)

For example, if C is your root and you have an Eb and a G, the resulting quality of the triad is minor. It’s a C minor triad, and here are its component intervals:

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

This principle applies to seventh chords as well. The component intervals of a seventh chord determine the quality of the 7th chord—or what kind of 7th chord it is.

First, we’ll look at the five basic types of 7th chords—

- The Major Seventh Chord (ex. Cmaj7)

- The Dominant Seventh Chord (ex. C7)

- The Minor Seventh Chord (ex. C-7)

- The Half-Diminished Seventh Chord (ex. C-7b5)

- The Fully-Diminished Seventh Chord (ex. Cdim7)

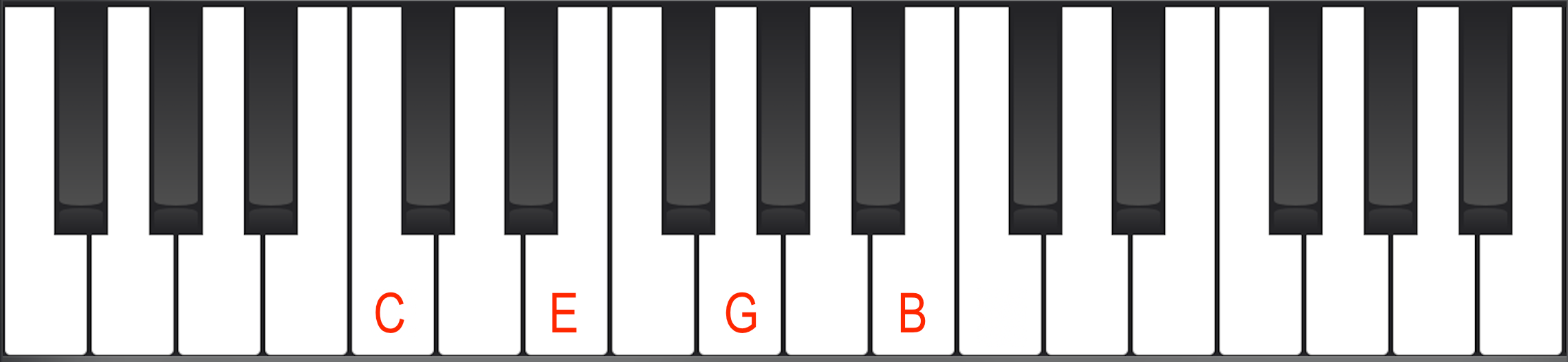

The Major Seventh Chord (and Major 6th Chord)

We’ve already introduced the C major seventh chord above. The major seventh chord diatonically functions as the (I) or the (IV) chord in the key of C major. Add a major 7th to the basic three-note C major chord to get a C major 7th chord.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Major 7th (B) or (7)

Here is this root position Major 7th Chord on Piano:

Here is this root position Major 7th Chord on Guitar:

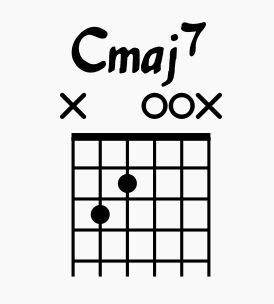

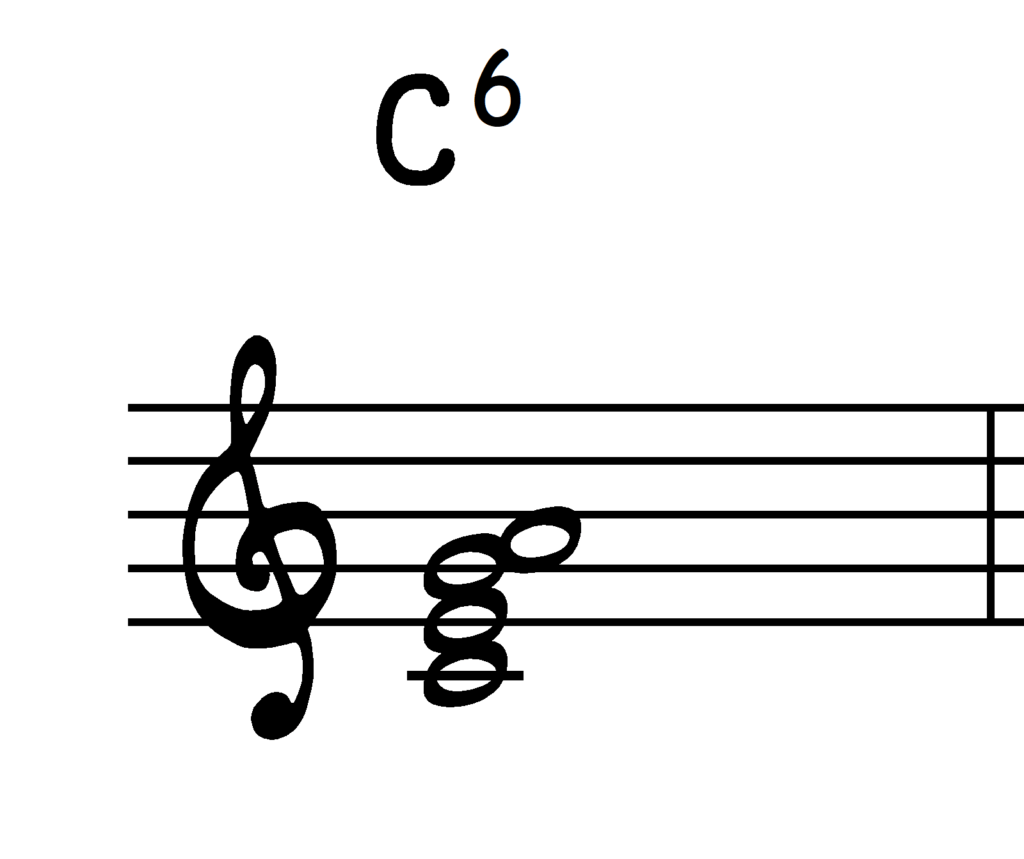

The Major 6 Chord

Major 6th chords were used much more frequently in earlier styles of jazz. Think of the classic jazz standard All of Me by Gerard Marks and Seymour Simon. Instead of starting on a major triad or a maj7 chord, the song begins on a maj6 chord. It functions as a tonic chord or a (I) chord.

To build it, you take a major triad and add a major 6th from the root or a major 2nd from the 5th:

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Major 6th (A) or (6)

Strict practitioners of music theory might argue that this shouldn’t have a category of its own because it’s technically a minor 7th chord in first inversion, but this is jazz. We have artistic license to bend and adapt the rules at our convenience!

It’s worth including it here because you’ll definitely encounter it if you haven’t already.

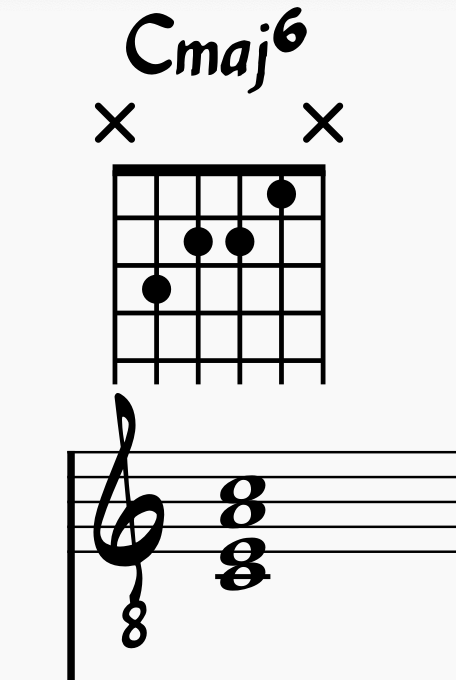

Here is a Cmaj6 voicing on guitar:

Because of the nature of the guitar, it’s sometimes impossible to get close root position voicings. Notice here we have to omit the G to put the A in this 7th chord. I reflected this change in the staff notation. Seventh chords built on guitar will sometimes not be playable in close root position.

Here is this 7th chord on piano:

The Dominant Seventh Chord

The dominant 7th chord is widely used in jazz. Diatonically, it functions as the (V) chord in major keys, but you’ll find dominant seventh chords all over jazz—especially in the blues.

You build a basic dominant chord by taking a major triad and adding an extra note: the minor seventh from the root or a minor 3rd from the 5th—

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

Usually, it’s used as a secondary dominant to lead to other diatonic chords in major and minor keys. It’s also used to change keys in jazz chord progressions. The basic jazz blues is made entirely of dominant chords.

Check out our blog post on 4 blues progressions you need to know.

A few examples of these secondary dominants include—

- the dominant (II7) chord (Bb7) in Donna Lee

- the dominant (VI7) chord (F7) used in Donna Lee

- the dominant (I7) chord (Ab7) used in Donna Lee to take us to the (IV) chord

- the dominant (III7) chord (E7) used in All of Me, to use an example from above

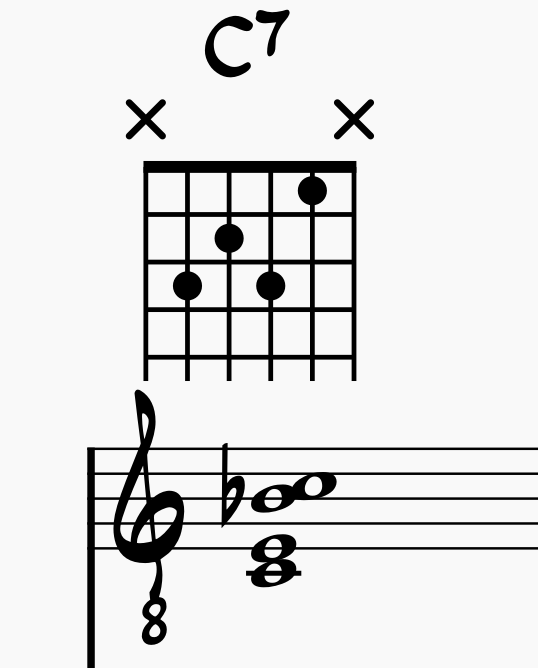

Here is a C7 chord voicing on Guitar:

Notice again how we have to change the notation on the staff to make this seventh chord possible on the guitar. (It will be a running theme with seventh chords built on guitar.)

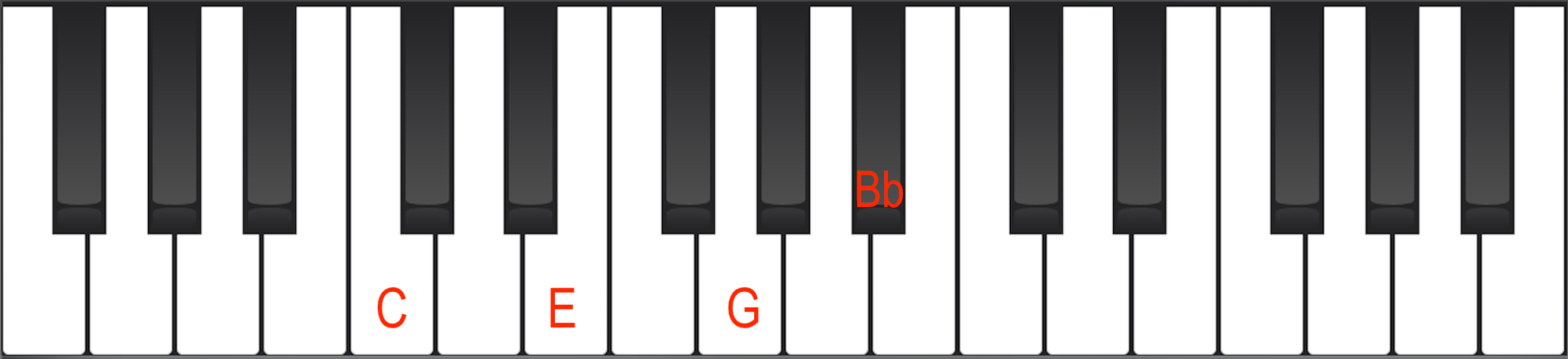

Here is a close root position C7 voicing on Piano:

Check out our podcast episode on understanding secondary and backdoor dominant chords to learn more about how these dominant 7th chords work.

The Minor Seventh Chord

The minor Seventh chord functions as the (ii7), the (iii7), and the (vi7) chords in major keys. There are also entire modal tunes composed using only minor seventh chords. Perhaps the most famous example is John Coltrane’s Impressions, but there are many more examples of tunes written exclusively with minor seventh chords.

Here are four more modal tunes you should add to your repertoire.

You build a minor seventh chord by taking a minor triad and adding a minor seventh interval from the root or a minor third interval from the 5th.

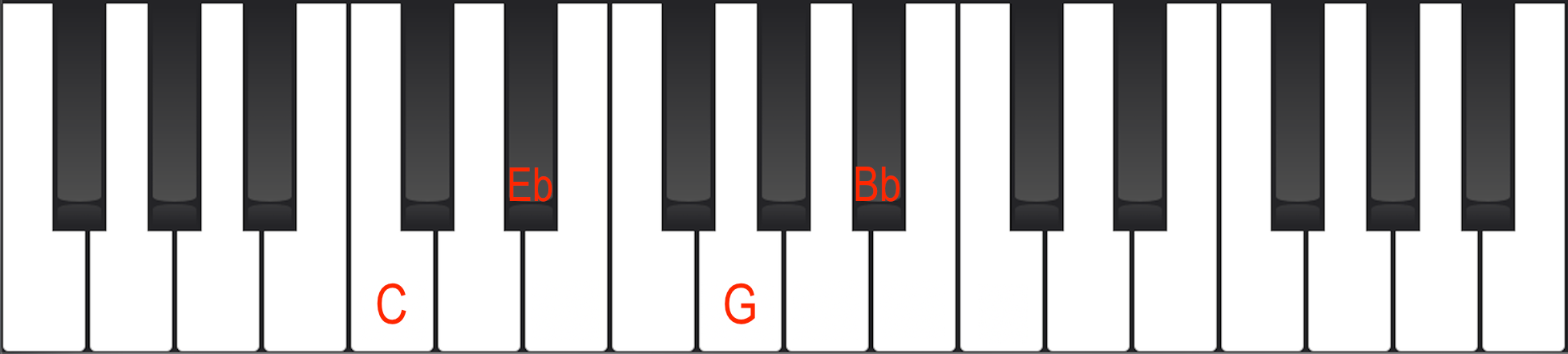

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor Third (Eb) or (b3)

- Perfect Fifth (G) or (5)

- Minor Seventh (Bb) or (b7)

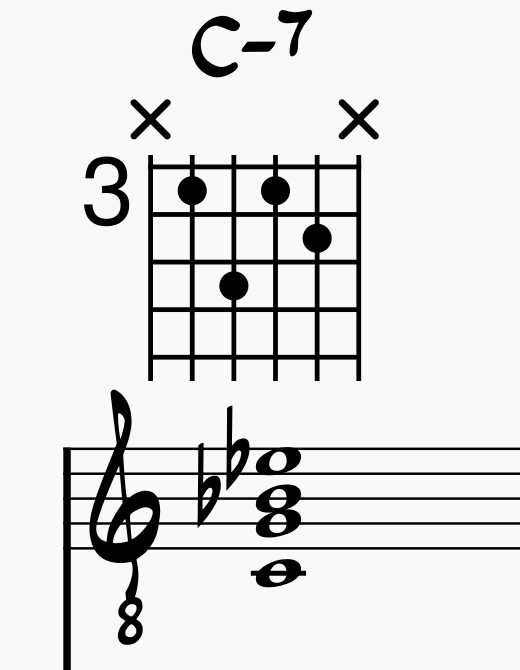

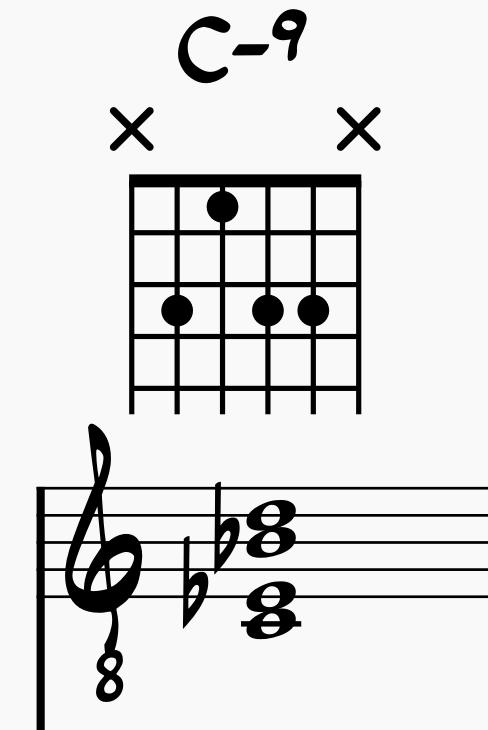

Here is a C-7 Chord on Guitar:

Here is a close root position C-7 chord on Piano:

The Minor 6 Chord

Yes, it’s also an A-7(b5) in first inversion, but the minor 6 chord deserves to have its own dedicated section.

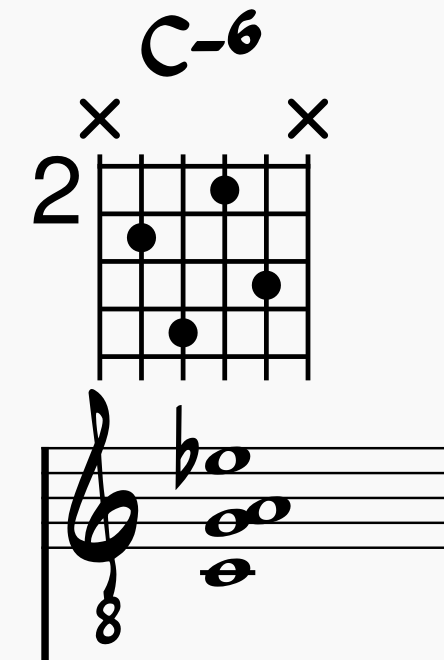

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Major 6th (A) or (6)

This chord is the backbone of many amazing jazz tunes that use minor keys.

- Round Midnight by Thelonius Monk

- Summertime by George Gershwin

- Minority by Gigi Gryce

- Alone Together by Arthur Schwartz

Here is a C-6 chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a close root position C-6 chord on Piano:

The Half-Diminished Seventh Chord

The minor 7(b5) chord, or half-diminished seventh chord, functions as the (viiø7) chord in major keys and is often used as the (iiø7) chord in a minor [iiø7 – V7 – i-7] progression. Half-diminished seventh chords work nicely because the b5 of the ii chord becomes a b9 on the (V7) chord before resolving to the 5th of the (i-7).

You build a half-diminished chord by taking a diminished triad and stacking a minor seventh interval from the root or a major 3rd interval from the (b5).

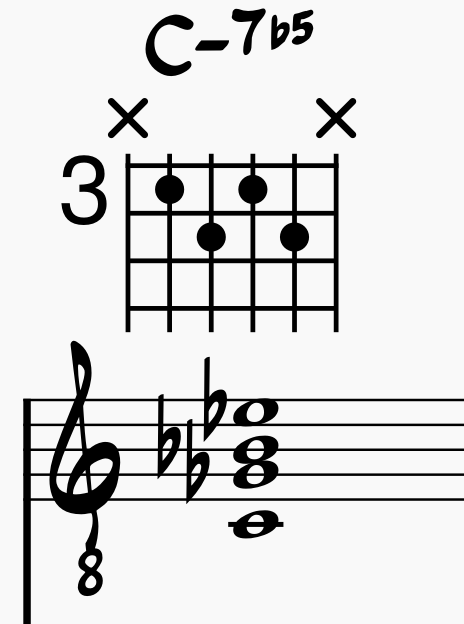

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Diminished 5th (Gb) or (b5)

- Minor 7th (Bb)

Here is a voicing for C-7b5 on Guitar:

Here is a C-7b5 chord on Piano:

The Fully-Diminished Seventh Chord

This diminished 7th chord is a non-diatonic chord and doesn’t exist in the major key. However, it is the leading tone 7th chord in the harmonic minor scale (it’s built from the seventh note of the scale).

The diminished seventh chord is used as a passing chord in jazz comping or as a substitute for a (VI7) chord. The first and second measures of Rhythm Changes are sometimes played like a [Imaj7 – VI7 – ii7 -V7]:

However, a chord player can substitute that dominant (VI7) chord for a (bii°7) chord. This 7th chord is a half step up from the tonic and has the same guide tones as the (VI7) chord but gives the progression a chromatic sound as it moves to the (ii7) chord in the second bar.

You can also replace the F7 in the second measure with a Dbdim7 chord that leads chromatically from the C-7 to D-7 (iii chord), which sometimes starts off the third measure.

Fully diminished seventh chords are built from diminished triads, with a diminished seventh interval added above the b5.

Diminished seventh intervals are enharmonically equivalent to major 6th intervals!

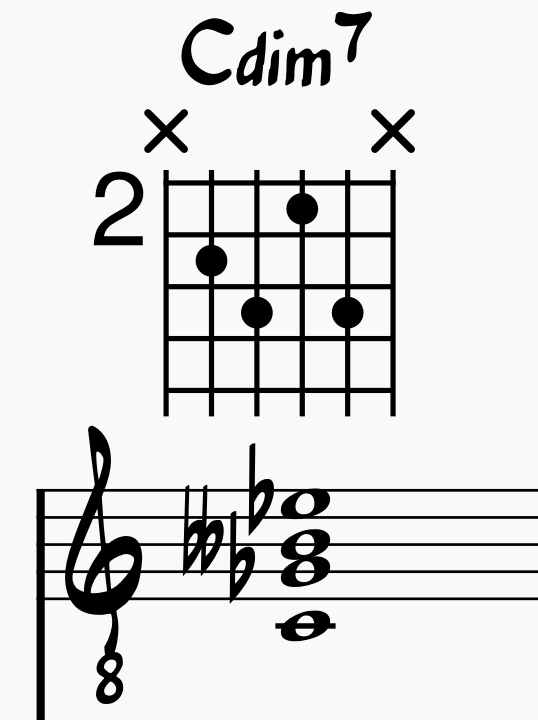

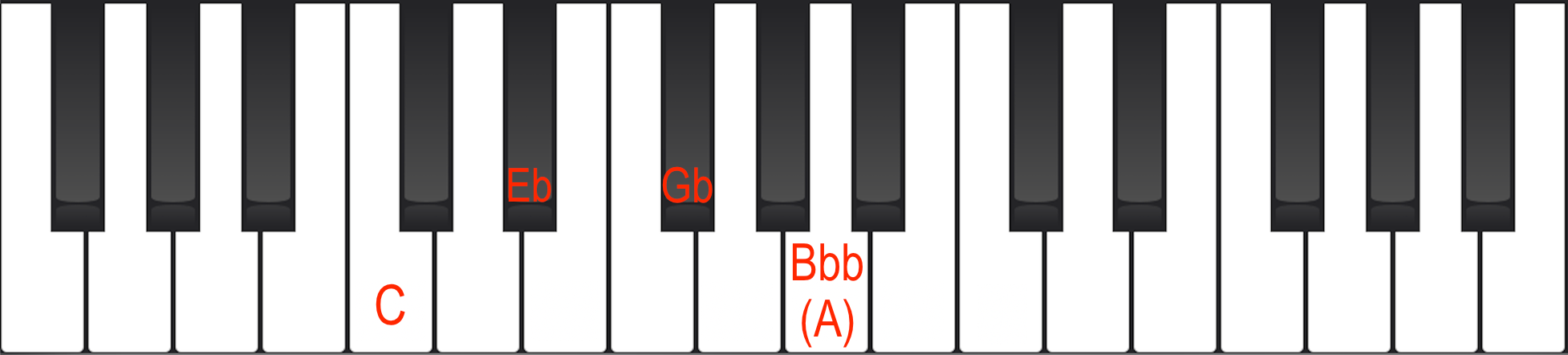

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Diminished 5th (Gb) or (b5)

- Diminished 7th (Bbb… that’s a double flat) or (bb7)

Here is a voicing for Cdim7 on Guitar:

Here is a Cdim7 chord on Piano:

Less Common Seventh Chord Qualities

The seventh chords listed above are the five most commonly encountered seventh chord qualities in jazz music, but jazz composers and improvers use plenty of other variations. Before we dig into the world of chord extensions, let’s quickly explore three less commonly used seventh chords.

Minor(Maj7) Chords

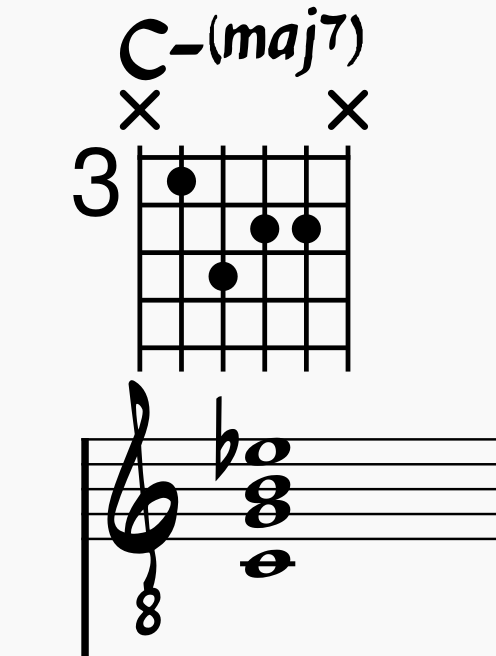

The minor major seventh chord is built by taking a minor triad and adding a major seventh interval from the root note or a major 3rd interval from the 5th.

- Rt. (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Major 7th (B) or (7)

You’ll often find minor chords with a major seventh in tunes that use a compositional device called the “wandering 7th.”

The jazz standard Blue Skies by Irving Berlin used this type of compositional device where the minor chord starts with a basic minor triad, and the next chord is a minor(maj7) chord, then a regular minor seventh chord, and finally a minor 6th chord. One of the voices in the chord moves downward chromatically and sometimes wanders back up—that’s where we get the name “wandering 7th.”

This chord is non diatonic. Though it can’t be built from the major scale, it can be built from some of the more flavorful minor scales—the harmonic minor and the melodic minor scales.

Here is a C-(maj7) chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a C-(maj7) chord on Piano:

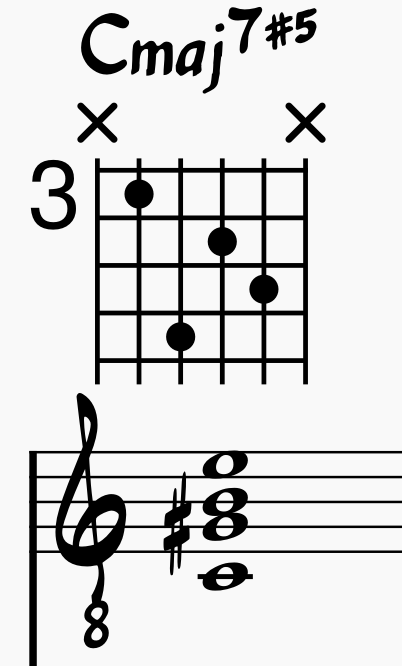

Augmented Major 7 Chords

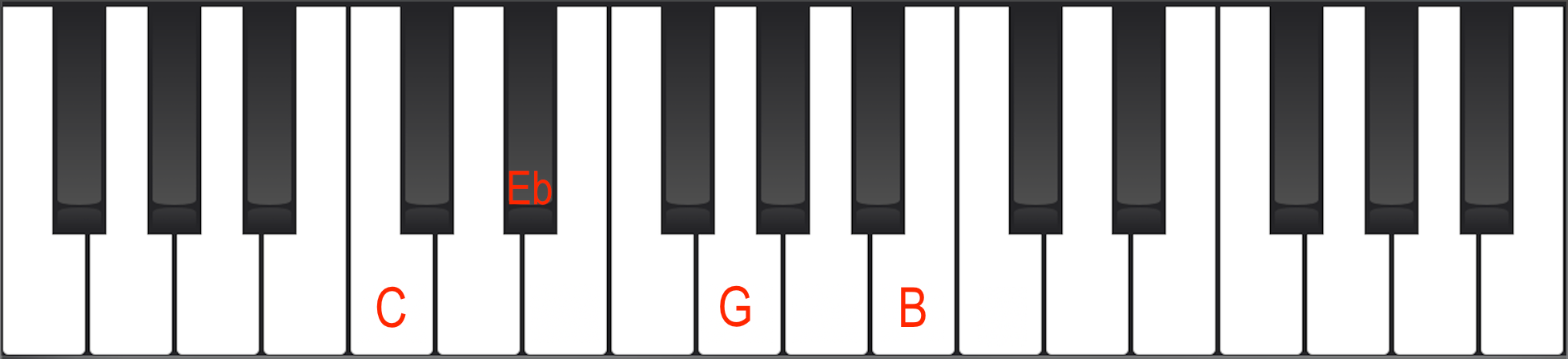

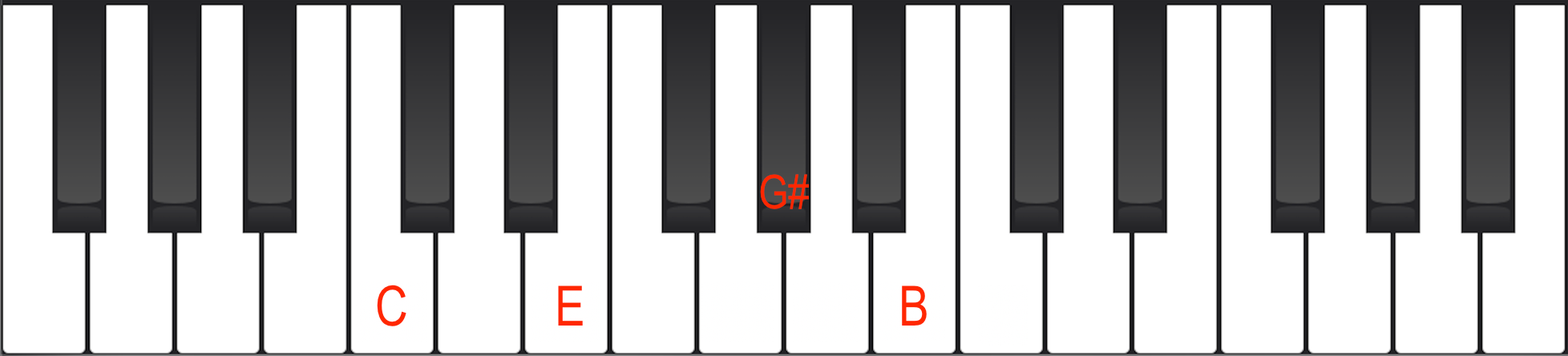

The augmented-major seventh chord is an augmented triad (major triad with a sharp 5th) and a major 7th. You can also think of it as a major 7th chord that has a sharp 5th, so it would be spelled [C-E-G#-B] instead of [C-E-G-B].

- Root note (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Augmented 5th (G#) or (#5)

- Major 7th (B) or (7)

This chord is unique and, when used appropriately, adds a beautiful and mysterious quality to music. Check out Wayne Shorter’s tune, Iris, for a great example of this chord in action.

Here is a Cmaj7#5 voicing on Guitar:

Here is a Cmaj7#5 chord on Piano:

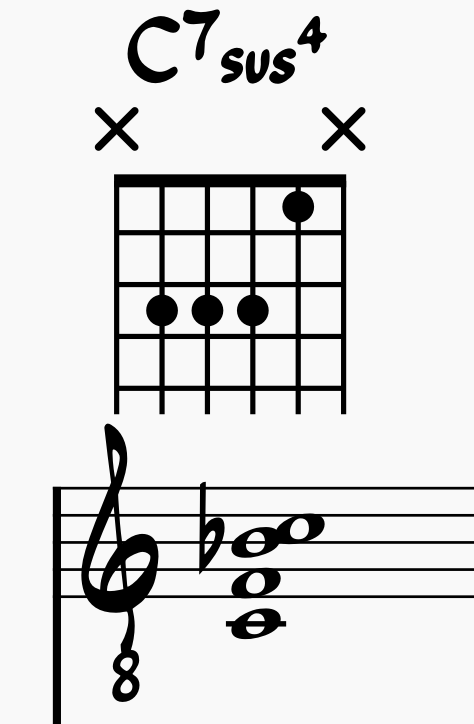

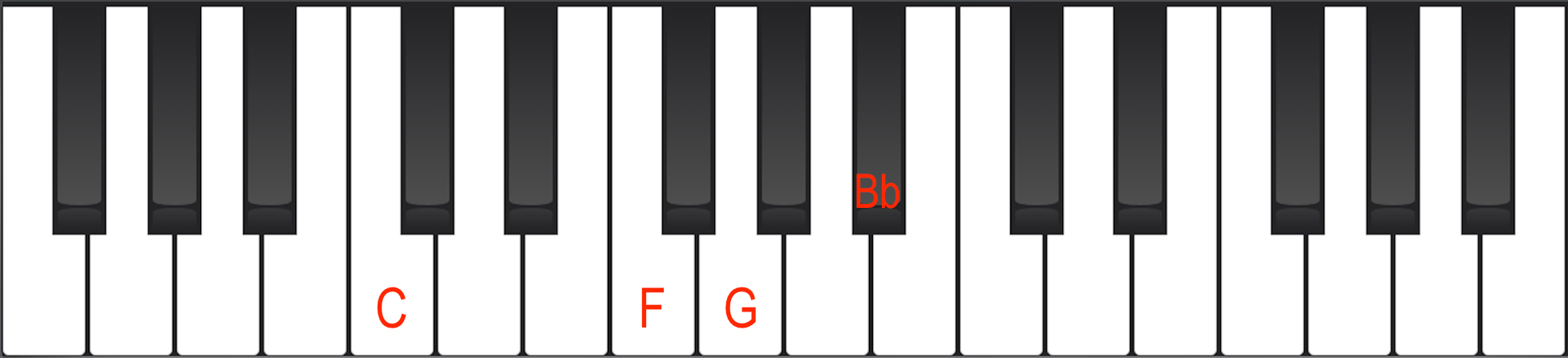

Dominant Sus4 Chords

The dominant sus4 chord is a dominant chord that replaces the 3rd with the 4th. Instead of being spelled [R – 3 – 5 – b7], it gets spelled [R – 4 – 5 – b7]. This chord is ambiguous because its quality isn’t really a major chord or a minor chord—it’s somewhere else.

- Rt. (C) or (1)

- Perfect 4th (F) or (4)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

Jazz composers use this chord to infuse their compositions with a floating sense of ambiguity. Fall, another Wayne Shorter tune, makes great use of this chord quality.

Here is a Dominant 7sus4 chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a C7sus4 chord on Piano:

7th Chords: Chord Extensions Past the 7th (adding the 9th, 11th, and 13th)

So that explains most seventh chords within the octave, but you’ve also probably encountered chords that have a (b9), (#9), (#11), or (b13) in their spelling. At first, this probably looks quite confusing, but there is a logic to it.

Here is the basic idea behind chord extensions:

For notes beyond the octave, we simply keep counting. When we stack thirds past the next octave, we get the notes of the major scale not expressed in the first octave—the 2nd, the 4th, and the 6th.

Major and minor 6 chords and the occasional sus2 or sus4 chord aside, we refer to the 2nd, the 4th, and the 6th by their distance away from the root in the first octave. What we get looks like this:

- Major 2nd + 7 = 9th

- Perfect 4th + 7 = 11th

- Perfect 6th + 7 = 13th

Musicians will often alter these extensions to either better fit the harmony of the moment or to create unique-sounding pitch environments to play over.

When you see chord symbols with extensions, you can subtract seven to figure out what scale degrees you need.

- E-9 chord – 7 = the second scale degree of an E minor scale (F#).

- C7#11 chord – 7 = an augmented (#) fourth scale degree of a C Mixolydian scale (F#)

- G13 chord – 7 = the 6th scale degree of a G Mixolydian scale (E)

Chord Extensions You’ll Encounter—

- (b9), (9), and (#9)

- (11) and (#11)

- (13 and (b13)

In traditional theory, every extension you add could contain the lower extension. 11th chords can include the 9th, and 13th chords will include the 11th and the 9th.

However, in practice, this doesn’t happen regularly. For example, a guitarist doesn’t have enough fingers or individual strings to build some of these chords. Therefore, in theory, a major 7th chord with a #11th on it could contain six notes—[C-E-G-B-D-F#]—but practically, the voicing is often less dense.

These extensions can be applied to any seventh chord quality: major seventh chords, minor seventh chords, dominant chords, and half-diminished seventh chords. However, in practice, the following chords are the most common.

BEFORE YOU CONTINUE...

If music theory has always seemed confusing to you and you wish someone would make it feel simple, our free guide will help you unlock jazz theory secrets.

Major Seventh Chord Extensions

Major 9th Chords

You construct major 9 chords by taking major seventh chords and adding the 9th above the root or a minor third above the 7th. By building a major 9th chord, you are taking a major 7th chord and adding a fifth note.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Major 7th (B) or (7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

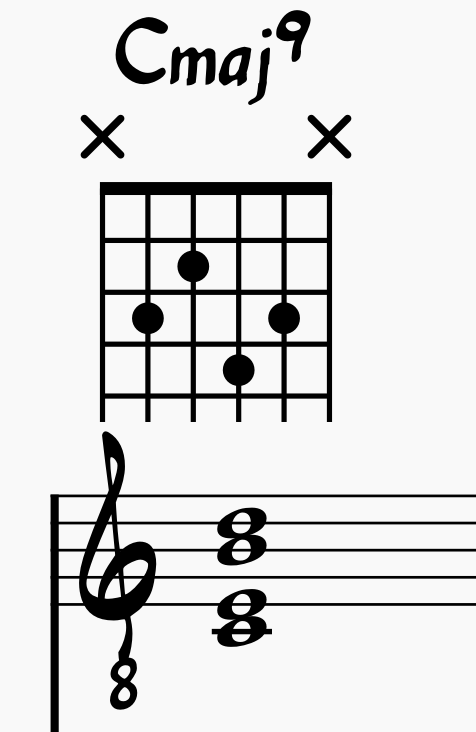

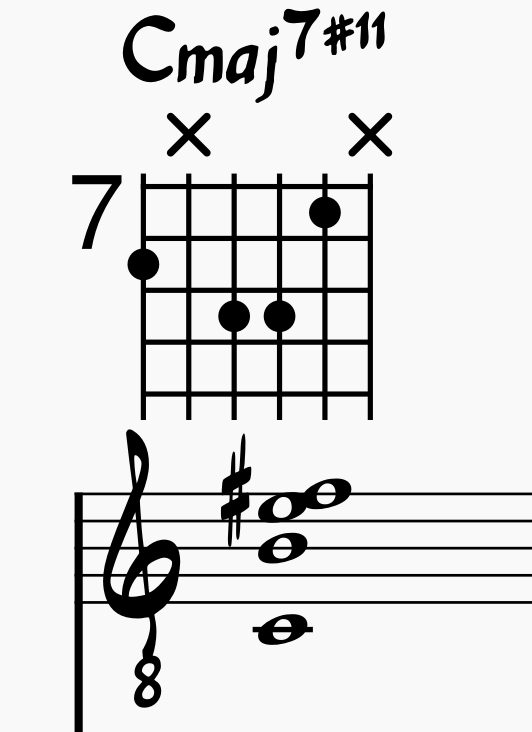

Here is a common major 9th chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a close position Cmaj9 chord on Piano:

Major 7(#11) Chords

Major 7(#11) chords are built by taking a major 9th chord and adding a sharp 11th from the root or a major 3rd interval from the 9th.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Major 7th (B) or (7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

- Sharp 11th (F#) or (#11)

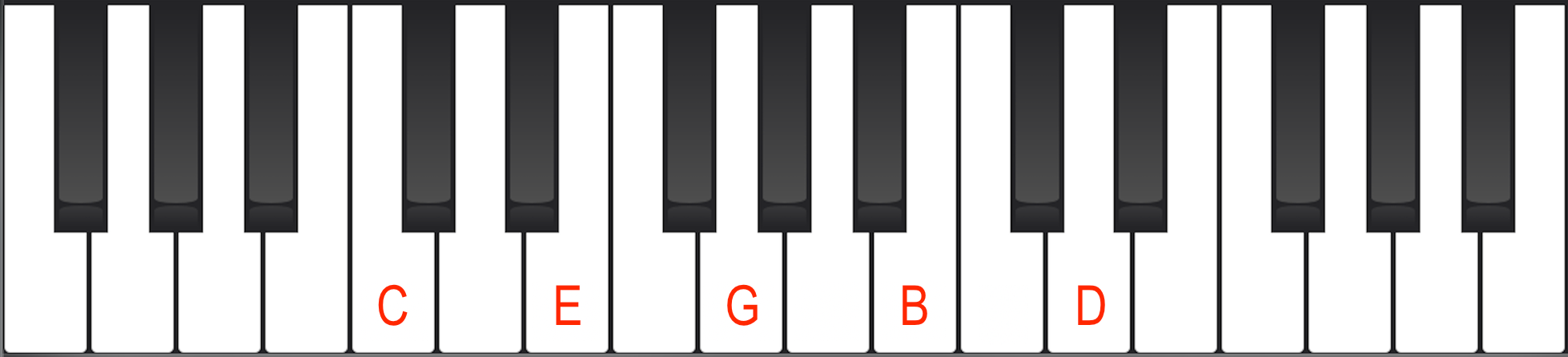

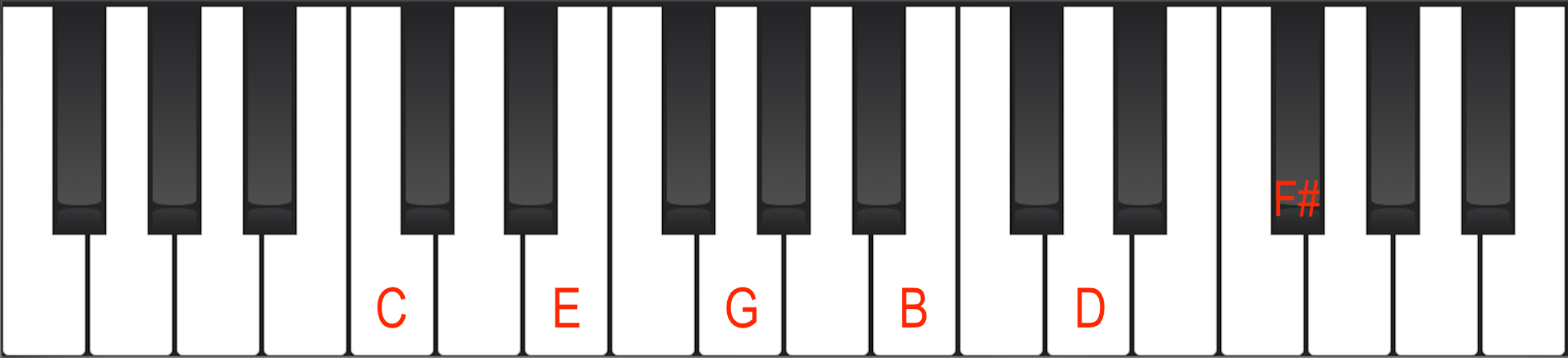

Here is a common Maj7#11 7th chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a close root position Cmaj7#11 chord on Piano:

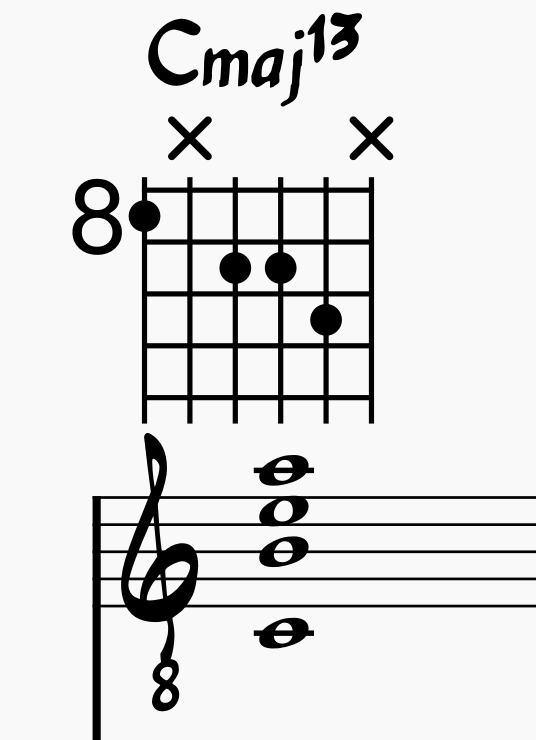

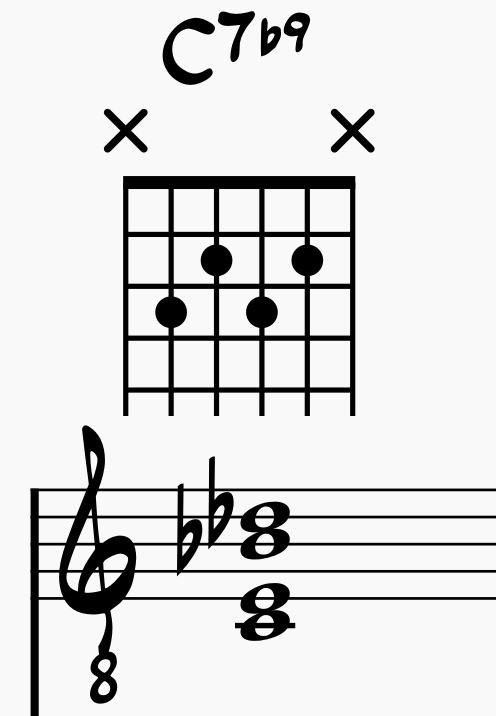

Major 13 Chords

When the 6th of the chord is in the 2nd octave, we call it a major 13 chord. Note that this chord doesn’t contain the 11th because it would clash with the 3rd in the lower octave. You build this chord by taking a major 9 chord and adding a 13th from the root or a 5th from the 9th.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Major 7th (B) or (7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

- Major 13th (A) or (13)

Here is a common Maj13 7th chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a close root position Cmaj13 7th chord voicing on Piano:

Dominant 7th Chord Extensions

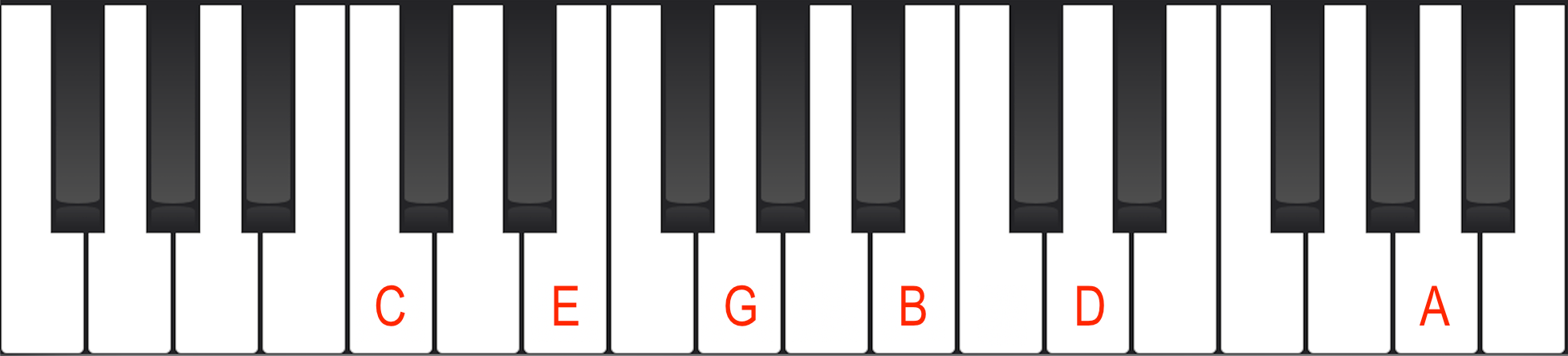

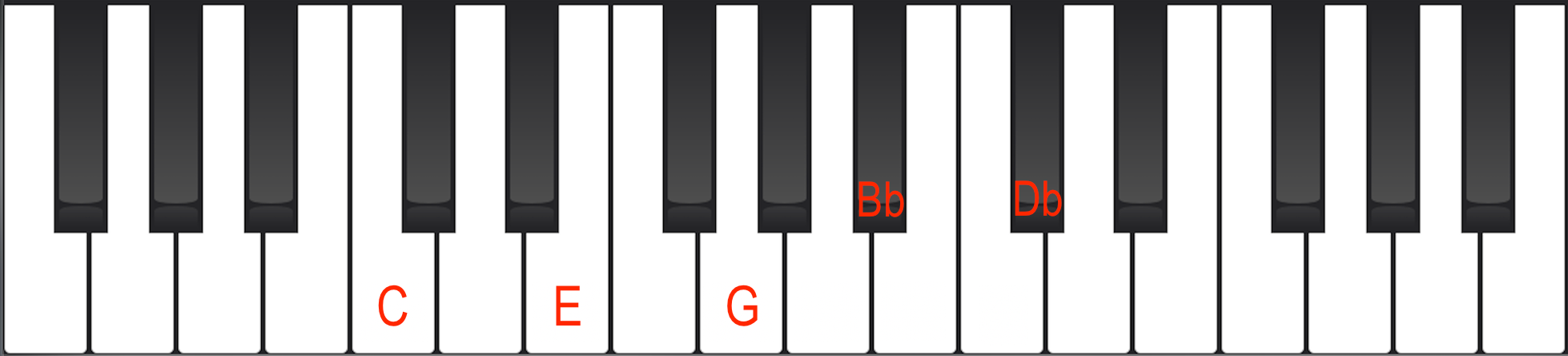

Dominant 7 (b9) Chords

The dominant 7 (b9) chord is built by taking a dominant 7th chord and adding a b9 above the root or stacking a minor 3rd onto the minor 7th interval. The relationship between the root and the b9 creates a distinct dissonance that makes this a powerful chord.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Minor 9th (Db) or (b9)

You can use dominant 7th chords like these when you see a 7(b9) or a 7alt chord symbol.

Here is a common C7b9 7th chord voicing for Guitar:

Here is a close root position voicing for a C7b9 chord on Piano:

Dominant 9 Chords

The dominant 9 chord is built by stacking an unaltered 9th on top of a dominant seventh chord or stacking a major 3rd on top of the minor 7th interval. You’ll hear this and other seventh chords all over blues music.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

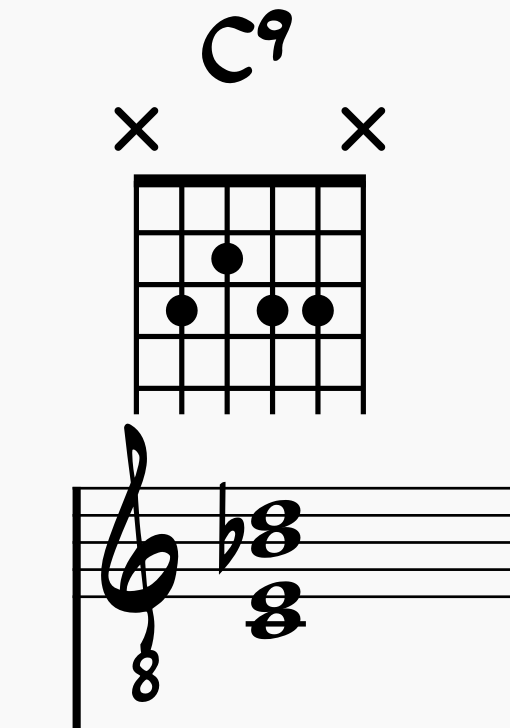

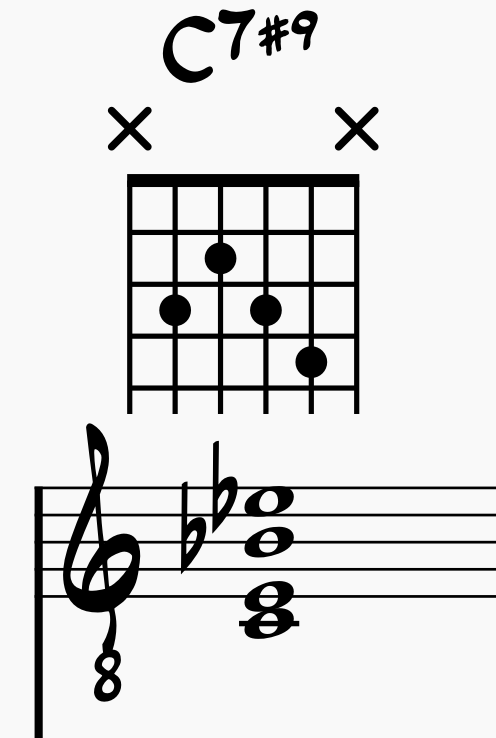

Here is a common 7th chord voicing for a C9 chord on Guitar:

Here is a close root position C9 chord on Piano:

Dominant 7 (#9) Chords

Rock musicians sometimes refer to this chord as the Jimmy Hendrix chord, but it is also widely used in funk, jazz, and other genres. The dissonance between the major third in the first octave and the #9 (minor third) in the second octave creates a distinct clash that makes this chord fun to sit on.

You build this chord by adding a sharp 9th to a dominant seventh chord or by adding a 4th above the 7th scale degree.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Raised 9th (D#) or (#9)

You can use this chord when you see a 7(#9) or a 7alt chord symbol.

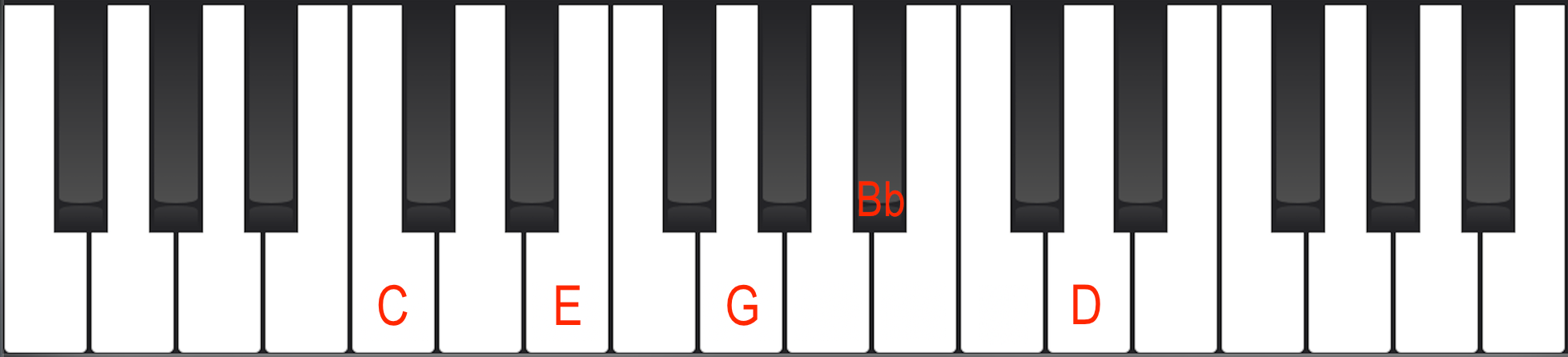

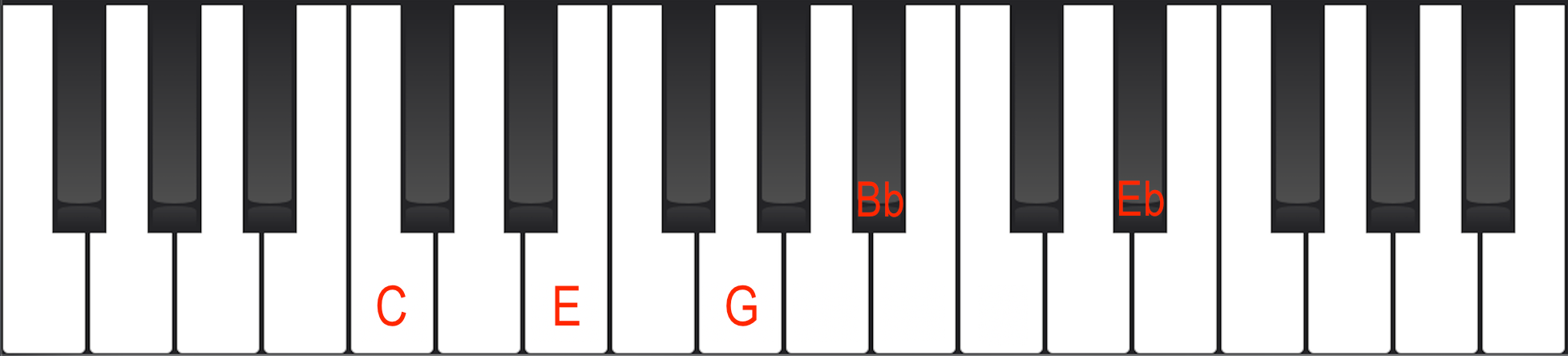

Here is a common voicing for a Dominant 7th chord with a sharp 9 on Guitar:

Here is a C7#9 chord in close root position on Piano:

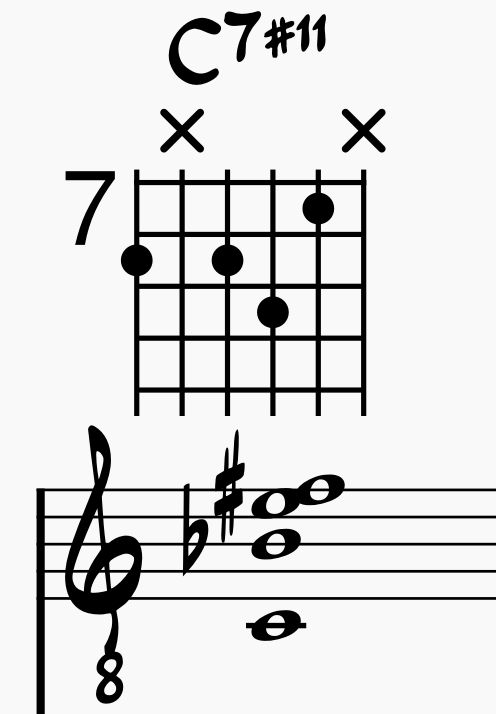

Dominant 7 (#11) Chords

The Dominant 7(#11) is Thelonius Monk’s favorite chord. It’s written into so many of his compositions…

- Monk’s Dream

- Monks Mood

- Pannonica

- Reflections

- Round Midnight

… to name a few.

This is a seventh chord built by taking a dominant 9 chord and adding a sharp 11 interval to the top. You can also think of it like stacking a major 3rd onto the 9th.

You’ll occasionally see this chord written as a Dominant (b5) chord. For example, a C7#11 can also be written as a C7b5.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

- Augmented 11th (F#) or (#11)

You can use this chord when you see a 7(#11) or a 7alt chord symbol.

Here is a common C7#11 chord voicing on Guitar:

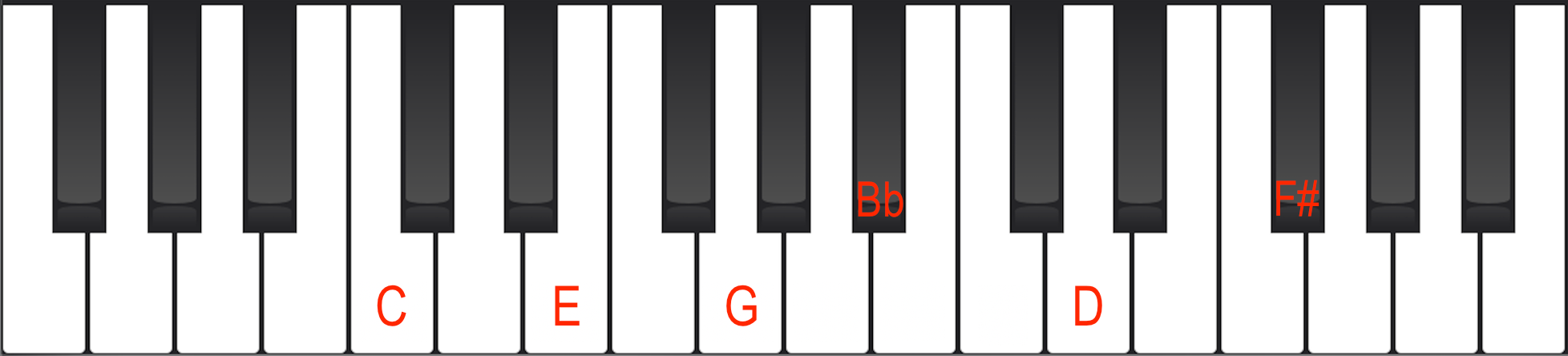

Here is a Dominant 7th chord with a sharp 11 on Piano:

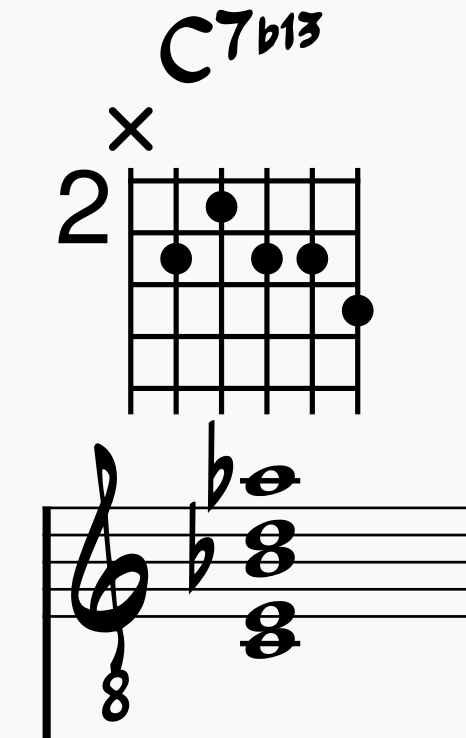

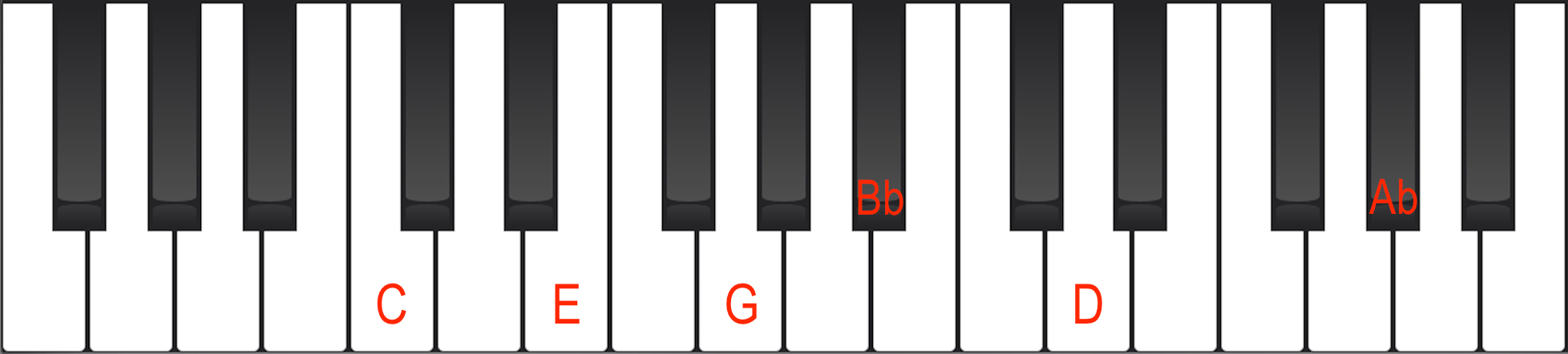

Dominant 7 (b13) Chords

You get a dominant 7(b13) chord when you take a dominant 9 chord and add a (b13) interval from the root or a (b5) interval from the 9th. Occasionally, this chord is spelled with a (#5) instead of a (b13). For example, C7b13 can also be spelled like C7#5.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

- Minor 13th (Ab) or (b13)

You can use this chord when you see a 7(b13) or a 7alt chord symbol.

Here is a C7b13 voicing on Guitar:

Here is a C7b13 chord on Piano:

Alt Chords

The last dominant chord we’ll mention today is the altered dominant seventh chord.

It’s kind of a catch-all dominant chord (except for the natural 9th and 13th). When you see this chord, you can assume that any and all crunchy tones are acceptable—the (b9), the (#9), the (#11), and the (b13) are all fair game.

You construct this chord by taking a dominant seventh chord, and you add the (b9), the (#9), the (#11), and the (b13).

- Root (C) or (1)

- Major 3rd (E) or (3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Minor 9th (Db) or (b9)

- Raised 9th (D#) or (#9)

- Augmented 11th (F#) or (#11)

- Minor 13th (Ab) or (b13)

Because these chords have so much variation, I’m not going to show examples. All of the altered extension seventh chords listed here can function as alt chords.

Minor 7th Chord Extensions

Minor 9 Chords

The minor 9 chord is constructed by taking a minor 7th chord and adding a 9 from the root or by stacking a major third from the 7th.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

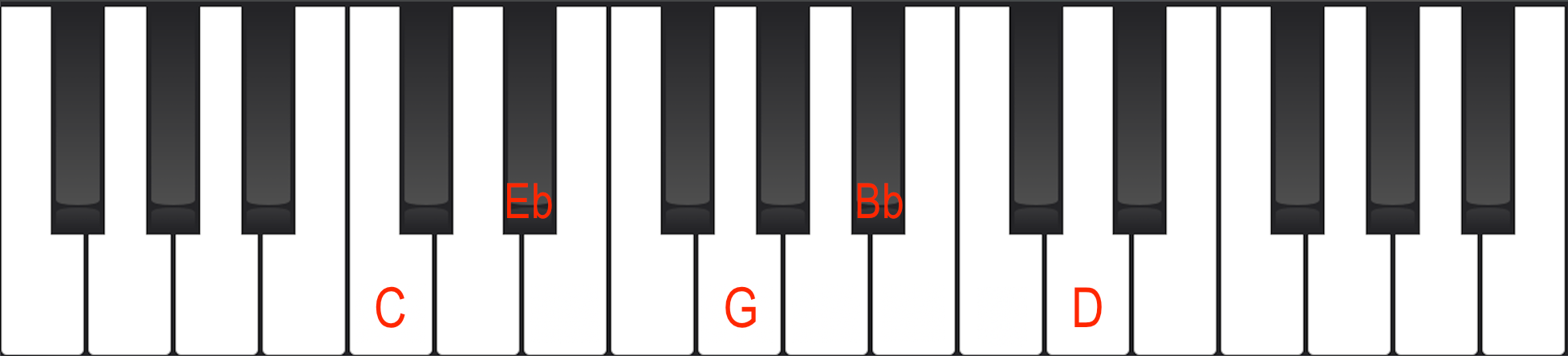

Here is a common C-9 chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a C-9 in close root position on Piano:

Minor 11 Chords

Minor 11 chords are constructed by taking a minor 9 chord and adding an 11th from the root or by stacking a minor third on top of the 9.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

- Perfect 11th (F) or (11)

These chords are useful for adding a suspended sound to your minor chords. You have the minor third in the first octave and a perfect 11th in the second octave. The major 9th interval between the 3rd and 11th of the chord creates an open sound.

Check our Wayne Shorter’s Footprints for a great example of this chord in action.

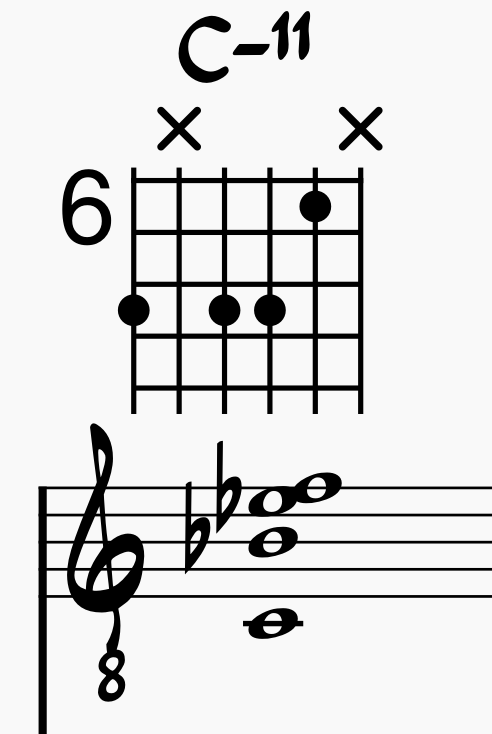

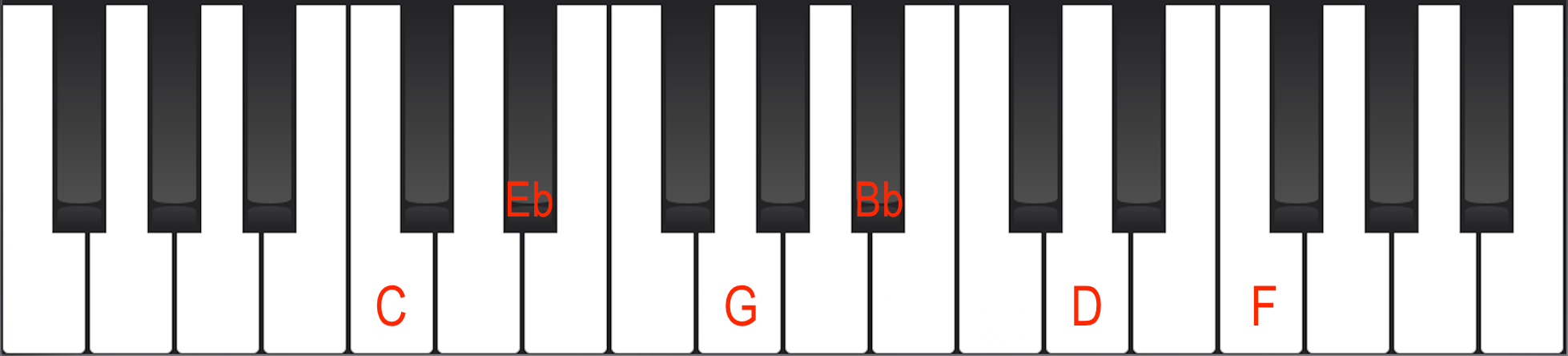

Here is a common C-11 chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a minor 11th chord on Piano:

Minor 13 Chords

Similar to the minor 6th chord, the minor 13th incorporates the 6th scale degree in the second octave. You build this chord by taking a minor 11th chord and adding a 13th above the root, or a major 3rd above the 11th.

- Root (C) or (1)

- Minor 3rd (Eb) or (b3)

- Perfect 5th (G) or (5)

- Minor 7th (Bb) or (b7)

- Major 9th (D) or (9)

- Perfect 11th (F) or (11)

- Major 13th (A) or (13)

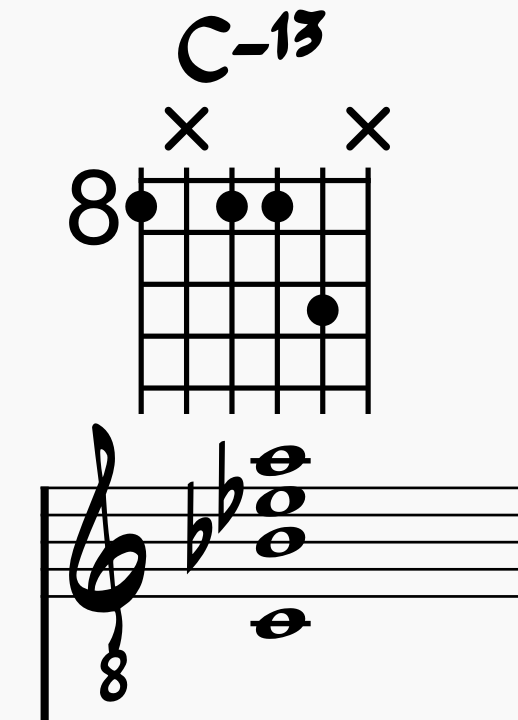

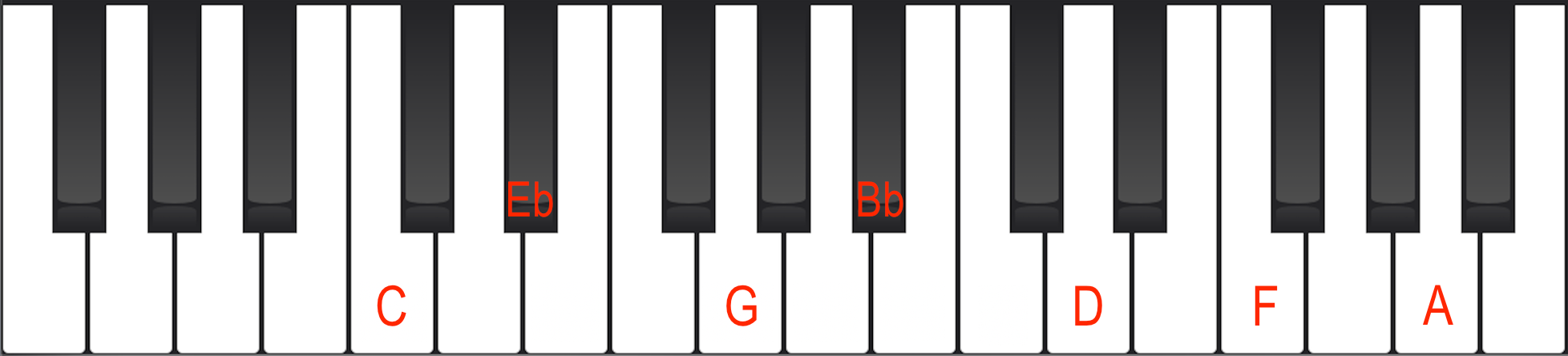

Here is a common C-13 chord voicing on Guitar:

Here is a C-13 on Piano:

Pro Tips For Reading 7th Chords on Chord Charts

We’ve covered practically every 7th chord and extension combination you can encounter! Take a second and soak that all in—it’s certainly a lot of information.

All memorized? Great!

So, where do we go from here?

It’s one thing to know how 7th chords and their extensions function, but it’s another thing to use this information to create music in the moment. Believe it or not, memorization is the easy part.

Artfully creating music with this information is the true goal of aspiring jazz musicians. Music isn’t really on the sheet music, after all. So, how can you practice all these 7th chords? How do you approach them in the wild? When reading a chart on a gig? Or in the studio?

Here are a few tips for reading chord charts—

Know All the 7th Chord Symbol Variations

The jazz tradition came about organically as the classical music traditions of Western music blended with Black folk music and blues in America’s big cities in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Because of this organic tradition, there wasn’t a set doctrine of how to talk about and communicate musical ideas. As a result, there are many ways to spell a single chord. Though today, chord symbols are relatively standardized, there are still variations you should be aware of.

Big “M” for Major Small “m” For Minor

CM7, a variation for Cmaj7, could easily be confused for a Cm7, which indicates a C minor 7th chord.

- CM6 vs Cm6

- CM7 vs Cm7

- CM9 vs Cm9

Maj and Min versus – and △?

Occasionally you’ll see a minor or major 7th chord written with these variations:

- Cmaj7 or C△7

- Cmin7 or C-7

Half-diminished or -7(b5)?

You see both ø and m7(b5) for the half-diminished seventh chord.

- Cø

- C-7b5

- Cm7(b5)

- Cmin7(b5)

Dim or °?

You’ll see diminished chords written as Cdim or C°.

It’s important to know all the different ways chords can appear. Otherwise, you may experience some uncomfortable moments on the gig!

Keep It Simple—You Don’t Need to Hit Every Extention (especially on altered chords)

Whether or not you are a chordal player, you may panic a bit when you come face to face with a Db7(b9#11#5) chord on a really fast tune. But remember, those are harmonic suggestions. You just need the basics.

Whether you are improvising or comping, you can definitely get by on this change with a simple Db triad. You don’t have to overthink it.

Want To Master Seventh Chords and Improve Your Knowledge of Jazz Harmony?

However, if your goal is to learn piano solos over complex changes or play chord solos on guitar like Kurt Rosenwinkel, you should check out Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

When you join the Inner Circle, you join a small circle of like-minded, motivated jazz musicians taking the right steps to improve their jazz playing and knowledge.

If you feel stuck and can’t seem to break through to that next level, check out the resources offered in the Inner Circle.

You’ll get access to—

- Monthly jazz standard studies to help you learn and improvise over jazz standards

- In-depth courses, practice programs, and personalized plans to help you improve quickly

- Instrument Accelerator courses to help you master your instrument.

- A diverse community of musicians who love jazz like you do.

Check us out and see what we’re all about! (The answer is jazz).