Modal tunes are an essential part of jazz repertoire. If you are new to jazz music, it won’t be long before you’ll encounter the term modal jazz. In fact, you’ve already likely heard modal jazz already.

Modal jazz refers to a style of jazz that uses modal harmony instead of tonal harmony (more on that later). Often, modal jazz focuses on a particular mode or tends to stay on a single chord for longer stretches of time.

As a jazz student, you’ll need to familiarize yourself with some modal jazz standards and work on modal playing, which presents unique sonic challenges. Modal improvisation can be deceptively challenging! How do you make one chord sound good for 16 bars?

This post will break down what modal jazz is theoretically, explore five easy modal jazz standards you should know, and discuss ways you can practice improvising over modal chord changes (or lack of changes!).

Are you looking to overhaul your jazz practice routine and supercharge your jazz chops? If so, check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

An Inner Circle membership grants you access to over ten years of incredible jazz education resources, including workshops, masterclasses, courses, and in-depth jazz standard studies brought to you by professional working jazz musicians.

Want to master modal improvisation? Come see what the Inner Circle has to offer!

Table of Contents

What Is Modal Jazz?

Modal jazz is a style of jazz that emerged in the late 1950s and 1960s, characterized by the use of musical modes rather than chord progressions as a harmonic framework.

Though modal music is far older, modal jazz represents a time in jazz history when certain jazz artists tried to redefine the genre and escape the harmonic restrictions of the bebop and hard bop eras.

The jazz from the bebop and hard bop eras was very tonal. Improvisational energy was focused on navigating the chord progression gracefully, virtuosically, and with attitude. Jazz artists interested in modal jazz, like Miles Davis and John Coltrane, wanted to explore improvisation from a different angle.

What could they say over one or two chords rather than a whole series of constantly changing chords?

It’s probably best to start with a few technical definitions so you understand the concepts behind the words modal and tonal.

Modality Vs. Tonality

The harmony in modal jazz is not tonal.

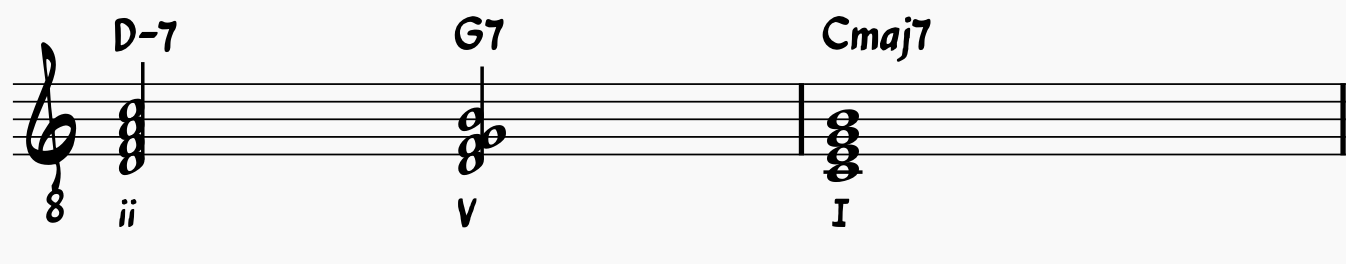

This means there isn’t a clear chord progression that leads to the tonic or tonal center. Tonal music uses functional harmony, where each chord has a logical function that brings you toward the tonal center as the progression progresses.

In ii-V-I chord progressions, the ii and the V guide your ear toward the resolution at the I, C major.

Modal jazz, on the other hand, has a tonal center, but all other chord changes in the composition are considered equal. There is no chordal hierarchy that values the tonic over other chords. In fact, some modal tunes can stay on one chord for the entire composition.

Modal chord changes can resolve tonally, or a composition can contain modal and tonal sections. Generally, there is less of a pull toward the tonal center in modal music than in tonal music.

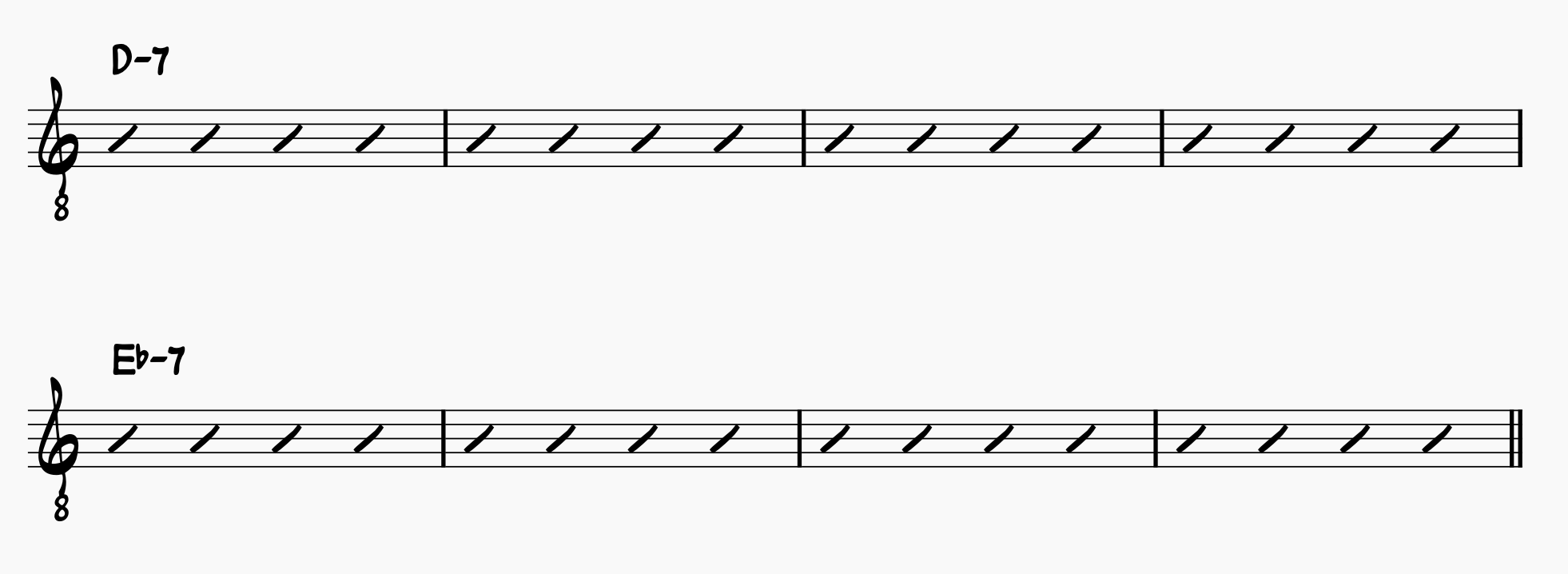

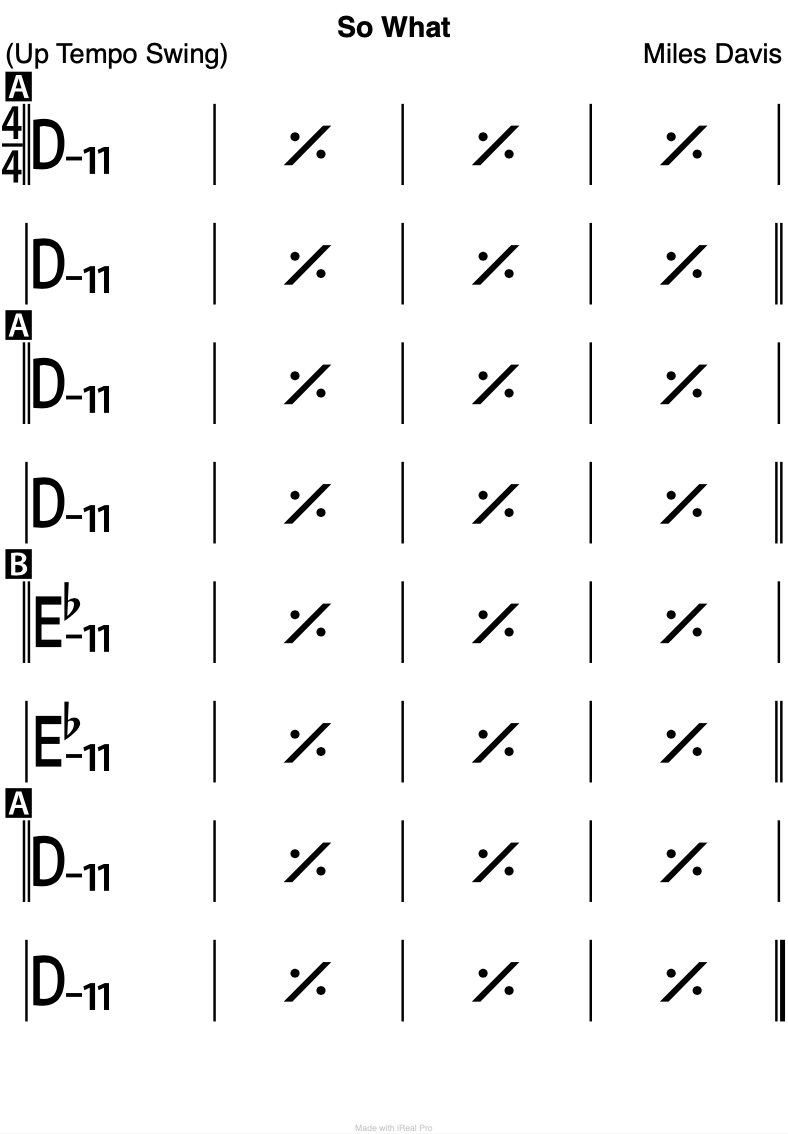

The following progression, based loosely on Miles Davis’s “So What,” is eight bars long and only has two chords. Plus, there isn’t a clear tonal function for each chord. Is the tonal center D-7, or is it Eb-7? The only harmonic change in the Miles Davis tune So What is that the D-7 moves up a half step to Eb-7.

The chord chart for “So What” says D-7 (or maybe D-11). But if you listen to the recording, pianist Bill Evans is doing much more than hanging on a D-7 chord for the entire A section. He creates motion and harmonic interest by playing other chords.

Modal Jazz Still Uses Diatonic Chords

Despite not being bogged down by functional harmony, modal tunes still utilize diatonic chords. Diatonic chords are built from the notes of the major scale or one of its derived modes.

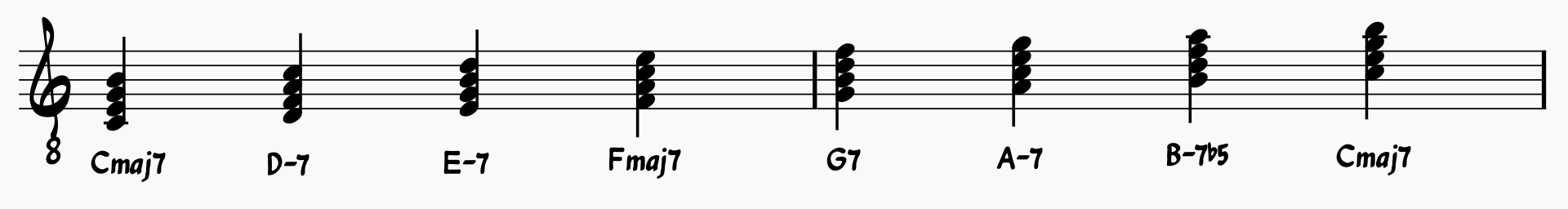

Here are the diatonic seventh chords in C major:

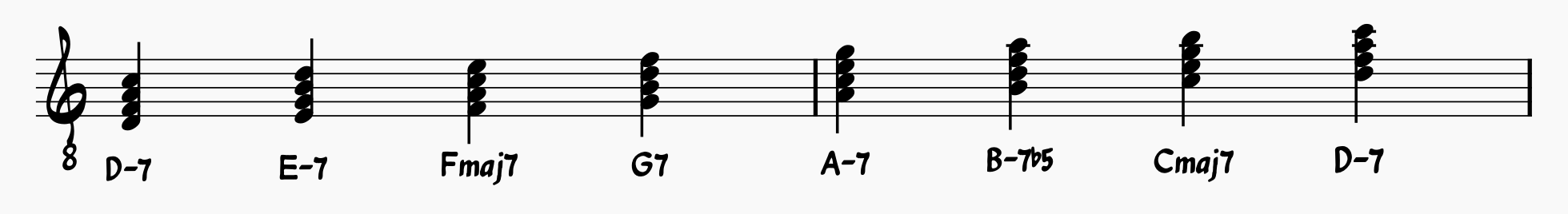

Modal jazz compositions written in the D Dorian mode will still use these same chords. However, there isn’t a strict progression. The modal approach isn’t about the destination. Rather, it’s about the atmosphere, the motion you can create, and the sounds you can squeeze out of sparse changes.

To refresh modes of the major scale, check out our guide to modes in music.

Quartal Harmony

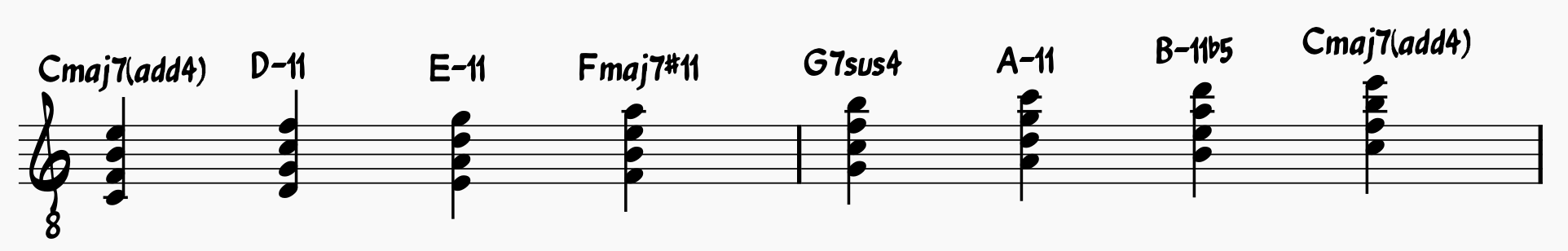

Often, chordal jazz players will use quartal harmony, which is harmony based on fourths, instead of the standard tertiary harmony, based on thirds. This obscures the tonal center even more, creating an open sound that allows the chord player to be freer with the changes.

- Construction: Quartal harmony deals with chords that are constructed by stacking fourths on top of one another. For example, a quartal chord might be C-F-B♭in the key of C.

- Sound: Quartal harmonies sound more open and ambiguous. They don’t have the built-in tonal functions we associate with traditional major and minor chords.

- Flexibility: Quartal chords don’t have the strong tonal identities of tertiary chords. As a result, they are useful in modal contexts where the composer or improviser wants to avoid implying a strong tonal center.

- Jazz and 20th-Century Classical Music: Quartal harmonies have been a staple in modern jazz, especially in the post-bop era. Musicians like pianist McCoy Tyner and many other jazz artists have made quartal voicings a crucial part of their sound.

Here is C major harmonized in quartal harmony:

For a refresher on 7th chords, check out our ultimate guide to 7th chords.

Other Characteristics of Modal Jazz

Apart from being modal rather than tonal, what makes modal jazz a distinct jazz style?

Harmonic Simplicity and Space Allows For Greater Freedom During Solos

Modal jazz often involves fewer chord changes than other jazz styles, which allows for more melodic freedom and exploration by jazz musicians. Soloists aren’t restrained by the constantly shifting harmonic landscape of tonal jazz music.

Normally, the soloist must pay attention to guiding tones and resolving tensions as the chord progression resolves. However, with modal jazz, this isn’t the focus. Often, jazz players will take extended solos over the tune, exploring the sound of a single chord.

Improvising solos and playing melodies over a particular chord for an extended period of time allows the improviser to explore many other improvisation concepts that the harmonic rhythm of tonal music might have otherwise restricted.

Mood and Atmosphere

Modal compositions often create a specific mood or atmosphere that remains relatively consistent throughout the piece. Listen to the modal jazz songs recommended in this article, and you’ll experience the mood and atmosphere firsthand.

Notable Jazz Musicians Who Played Modal Jazz (And Albums You Should Check Out)

Miles Davis

Kind of Blue (1959)

The album Kind Of Blue can’t seem to absorb enough praise! Tracks like “So What” and “Flamenco Sketches” are prime examples of modal jazz.

John Coltrane

A Love Supreme (1965)

While Coltrane famously explored many styles and playing philosophies throughout his career, A Love Supreme best showcases his modal approach to jazz music.

Bill Evans

Sunday at the Village Vanguard (1961)

Bill Evans, the pianist on (most of) Kind of Blue, deeply understood harmony, allowing him to shine when playing modal jazz.

Herbie Hancock

Maiden Voyage (1965)

This album is a masterpiece of modal jazz. Every tune is a masterpiece!

Wayne Shorter

Speak No Evil (1966)

Wayne Shorter’s compositions combine hard bop and modal influences. Speak No Evil has many great examples of modal music.

McCoy Tyner

The Real McCoy (1967)

As Coltrane’s pianist during his classic quartet period, Tyner was familiar with modal jazz. His own albums, like “The Real McCoy,” showcase his harmonic approach to modal tunes.

Joe Henderson

Inner Urge (1966)

The title track of this Inner Urge is a prime example of Henderson’s modal composition style, which often combines complex harmonies with various aspects of modal jazz.

Chick Corea

Now He Sings, Now He Sobs (1968)

Corea’s groundbreaking trio album showcases Chick Corea’s incredible sense of time and harmony.

Five Modal Jazz Tunes You Should Learn!

Here are 5 Easy Modal Jazz Standards to learn:

1. “So What” By Miles Davis; Kind Of Blue (1959)

So What: Miles Davis’ landmark album Kind of Blue opens with this modal tune. Though it’s only two chords for the entire 32-bar form, it’s actually quite easy to get lost!

We have a full study of this song in our Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

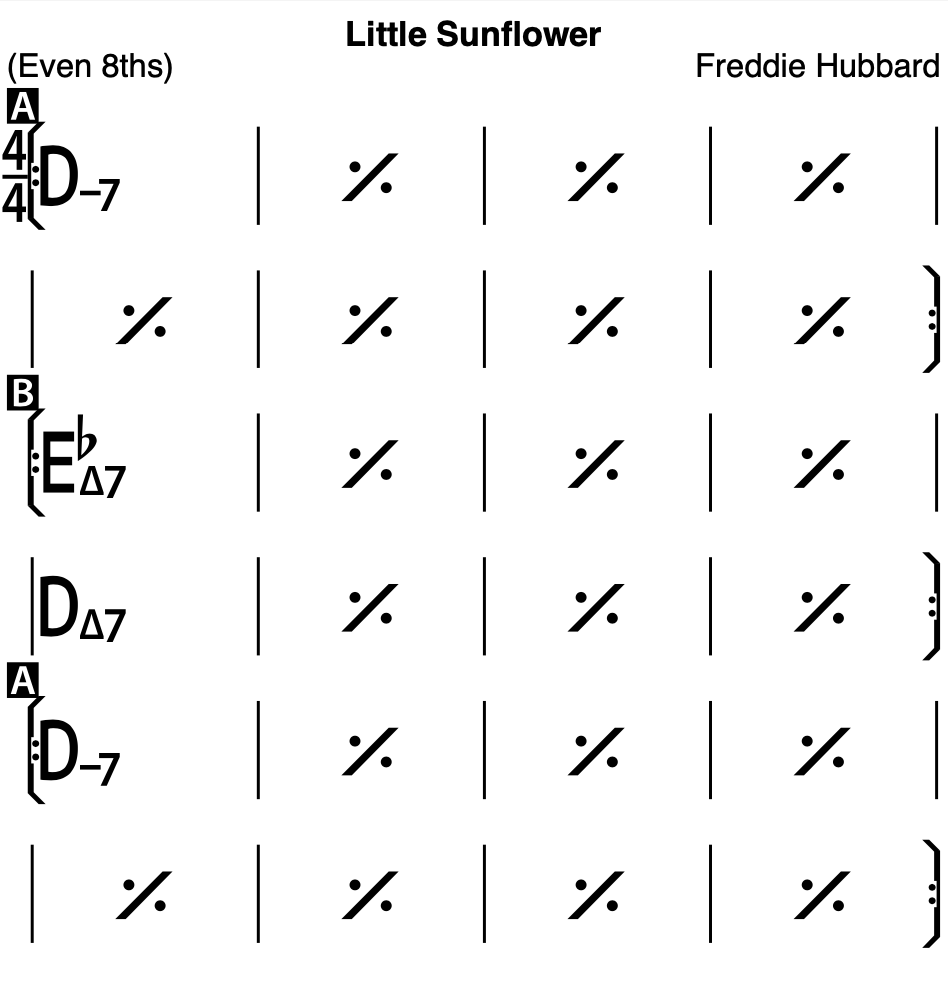

2. “Little Sunflower” By Freddie Hubbard; Backlash (1967)

Little Sunflower: This even 8ths Freddie Hubbard tune is a blast to play and allows the improviser to practice solo ideas and licks in major and minor tonalities.

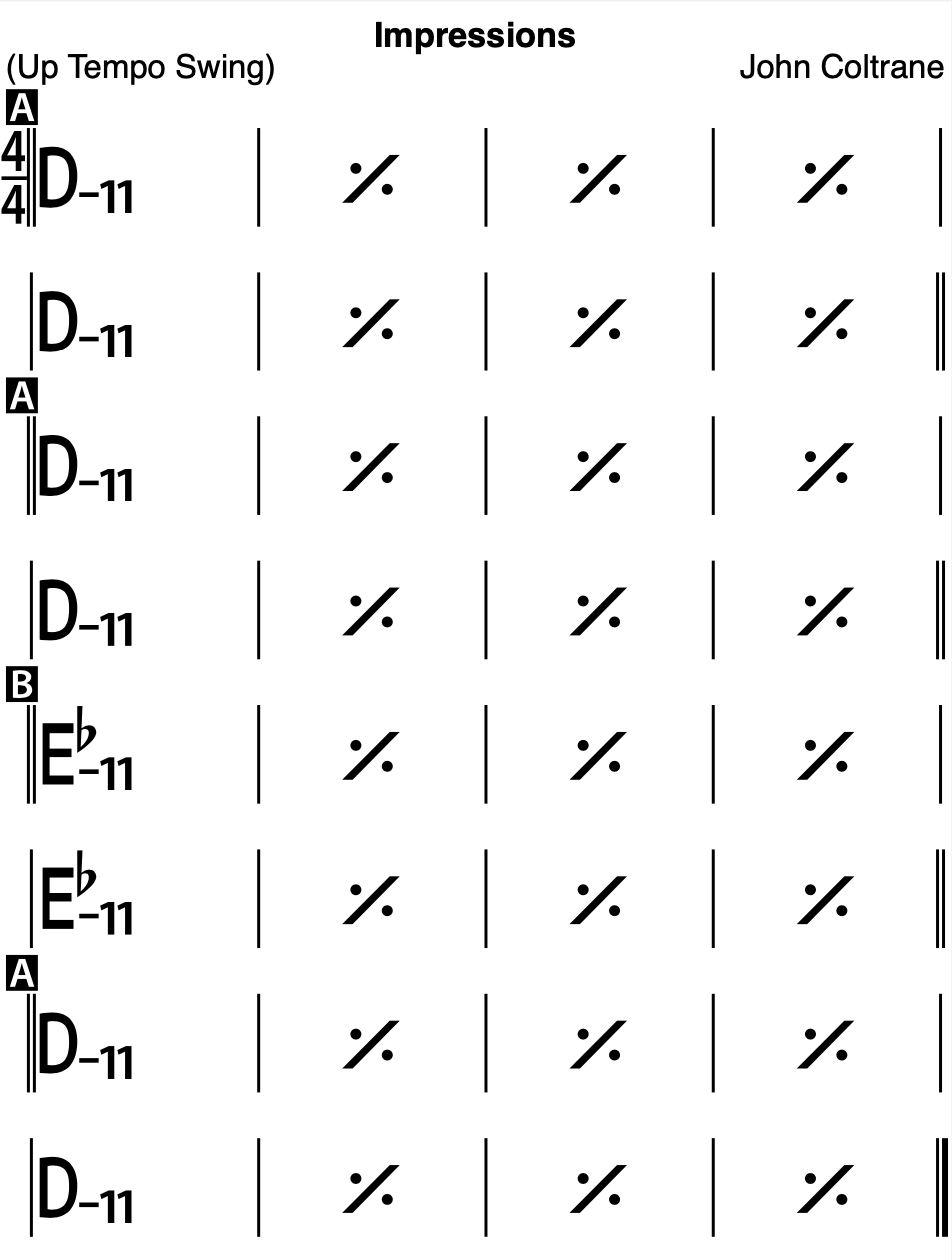

3. “Impressions” By John Coltrane; Impressions (1963)

Impressions: This is John Coltrane’s contrafact of “So What.” Though “Impressions” is played much, much faster.

We have a full study of this song in our Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

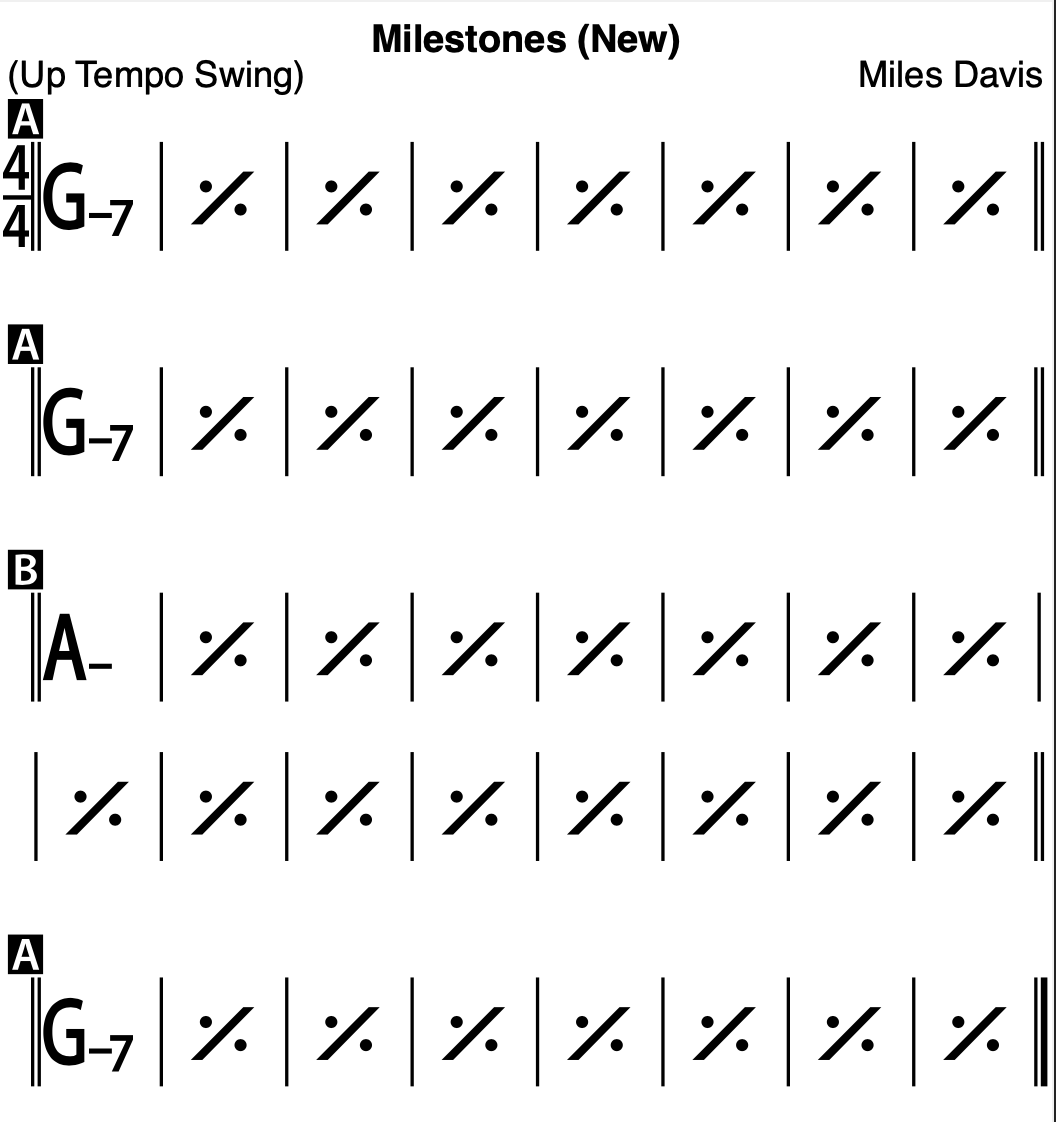

4. “Milestones” By Miles Davis; Milestones (1958)

Milestones: There are a few versions of this tune. One has more traditional harmony, and the other takes the modal approach. The modal version has only two key centers: G minor and A minor).

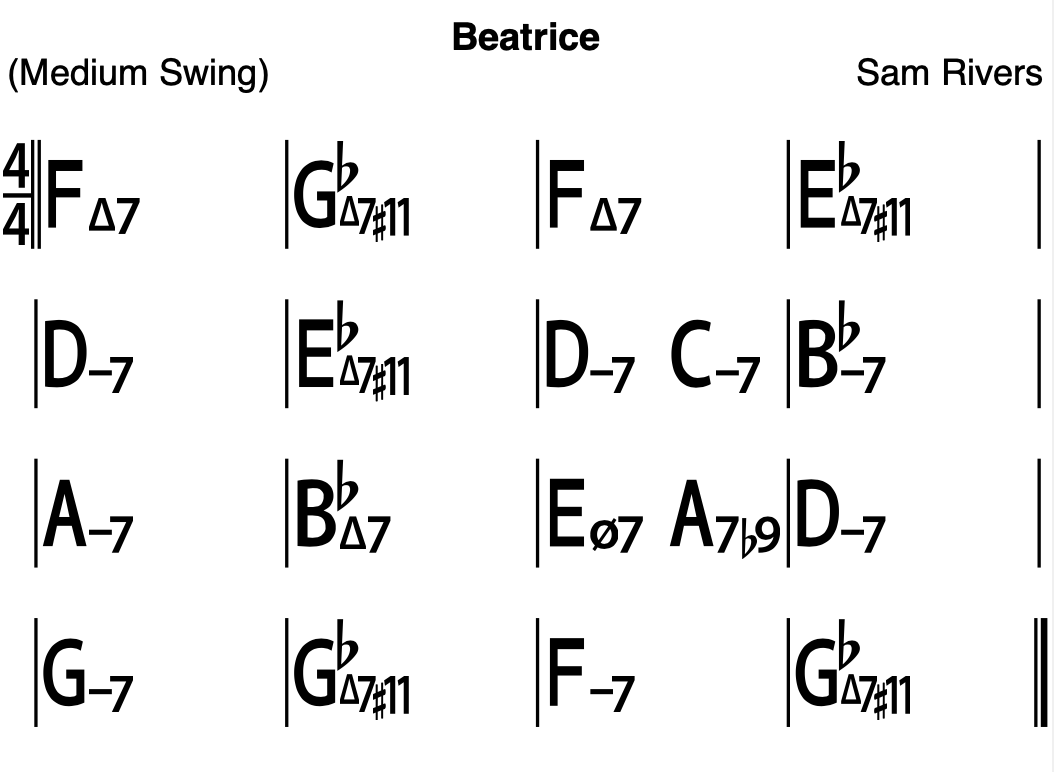

5. “Beatrice” By Sam Rivers; Fuchsia Swing Song (1964)

Beatrice: This tune is a great example of a single composition blending tonality and modality. There are modal aspects to it, like the maj7 chords moving in half steps, but there is also a section where tonality takes over, and the tune resolves to D-.

We have a full study of this song in our Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

Become The Best Jazz Player You Can Be! Join The Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle

Do you want to sound your very best but don’t know how to improve your jazz playing? If you feel stumped in the practice room, then you should check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

The Inner Circle has everything you need to systematically take your jazz playing to the next level. From masterclasses and workshops to instrument-specific jazz courses, the Inner Circle is designed for players who want to get to the next level.