Learning jazz licks is a great way to have a hands-on experience with the jazz language. Jazz licks—especially ones taken from or inspired by the jazz greats—help you think like a great jazz improviser.

This article will put you in the pilot seat and help you to start thinking about harmony and melody like a jazz musician. We’ll explore 20 jazz licks you can use over common jazz chord progressions.

Some of these licks are inspired by the jazz licks of the great jazz masters. Others are useful studies for outlining the changes by hitting chord tones, extensions, and alterations.

If you are ready to take your jazz playing to the next level and want unlimited access to more jazz material like this, check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle.

The Inner Circle has an incredible array of jazz education resources—including masterclasses, workshops, jazz standard deep dives, and many courses on all aspects of jazz theory, improvisation, and philosophy.

Ready to upgrade your jazz playing? Join the Inner Circle.

Table of Contents

Why Learn Jazz Licks?

When you are learning a language, you often memorize phrases that help you express basic ideas and questions. “Where is the train station?” or “What is your name?”

You might not know the meaning and function of every word in the sentence, but you know what the phrase means as a whole and can use it to functionally start speaking with others.

Learning the jazz language works in the same way.

Licks are like sentences improvisers use to express musical ideas. If you learn these licks and transpose them into all twelve keys, you’ll be practicing the jazz language in a bunch of different contexts, and you’ll have 20 musical phrases you can use on a gig or at a jam session.

Then eventually, you’ll adapt and evolve these licks to better fit your own unique voice.

That’s the value of learning jazz licks!

Elements of Jazz Language

Before diving headfirst into these licks, let’s talk a bit about the elements of jazz vocabulary. Though every player has a unique voice, some elements of jazz language are fairly universal.

Apart from scales, the following jazz licks will be mainly comprised of the following elements:

- chord outlines

- chromatic passing tones

- enclosure figures

- chromatic approach tones

Chord Outlines

Chord outlines are exactly what they sound like—they outline the basic chord tones present in the harmony of the moment. These are your basic triad and seventh-chord arpeggios with occasional extensions and alterations.

Here is a line that outlines a D-9 chord:

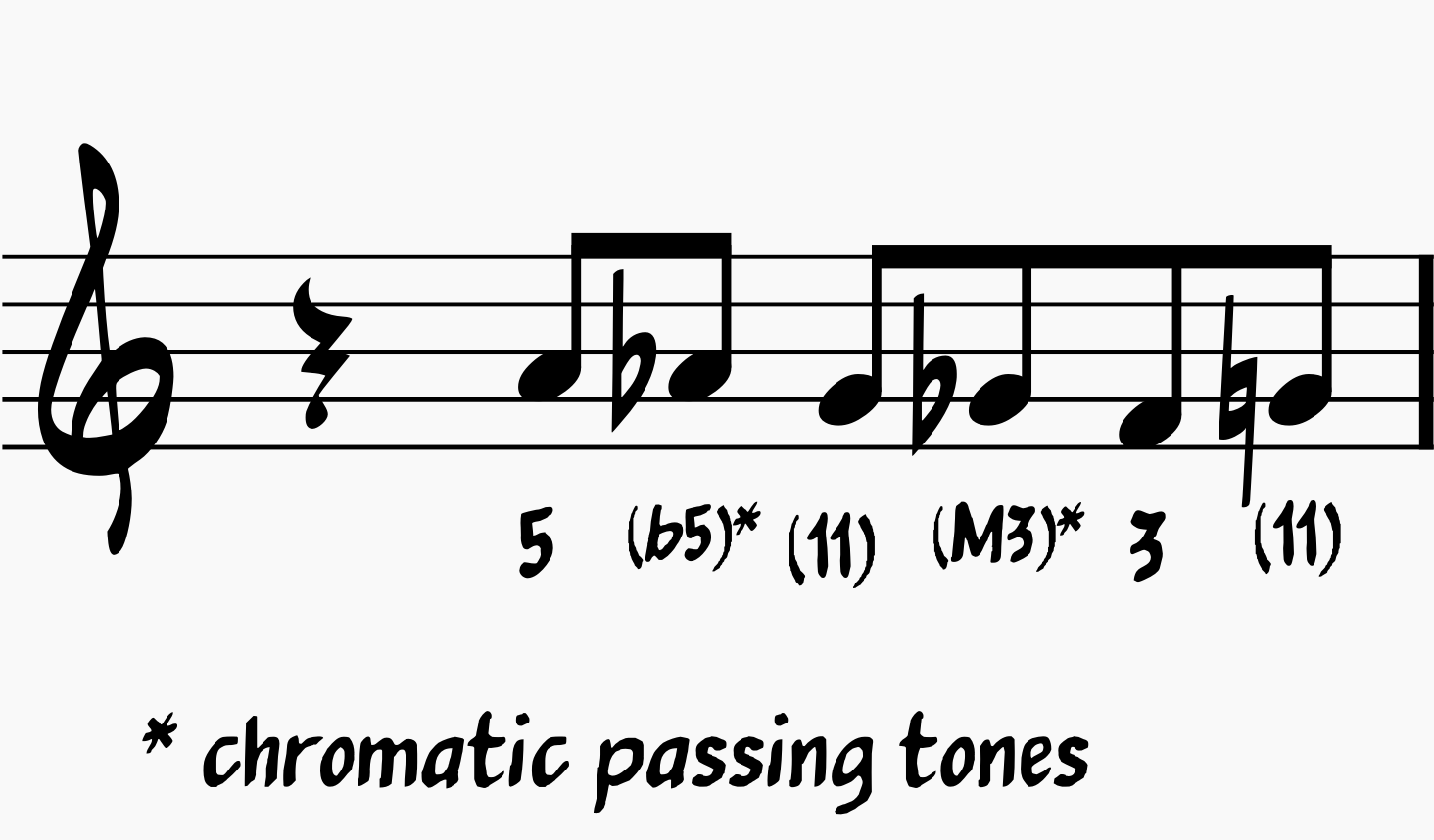

Chromatic Passing Tones

Chromatic passing tones are notes added to a scale or line to ensure that a chord tone falls on a strong beat. Chromatic passing tones are built into bebop scales.

Using chromatic passing tones, the soloist can keep D-7 chord tones on strong beats:

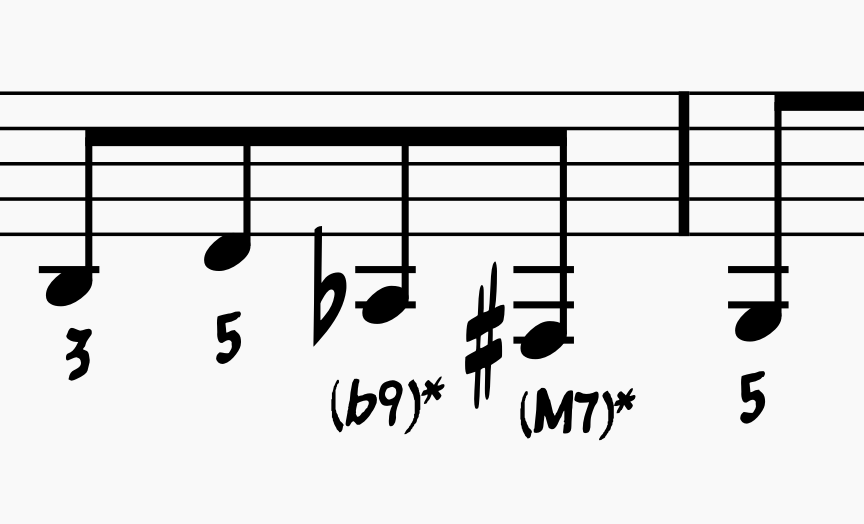

Enclosure Figures

This jazz device encloses or surrounds a target note, usually a chord tone. The enclosing notes can be chromatic or diatonic (meaning one or more of these notes can come from the scale, but they don’t have to).

Here, the Ab and F# enclose the G, which comes in on beat 1 of the second measure:

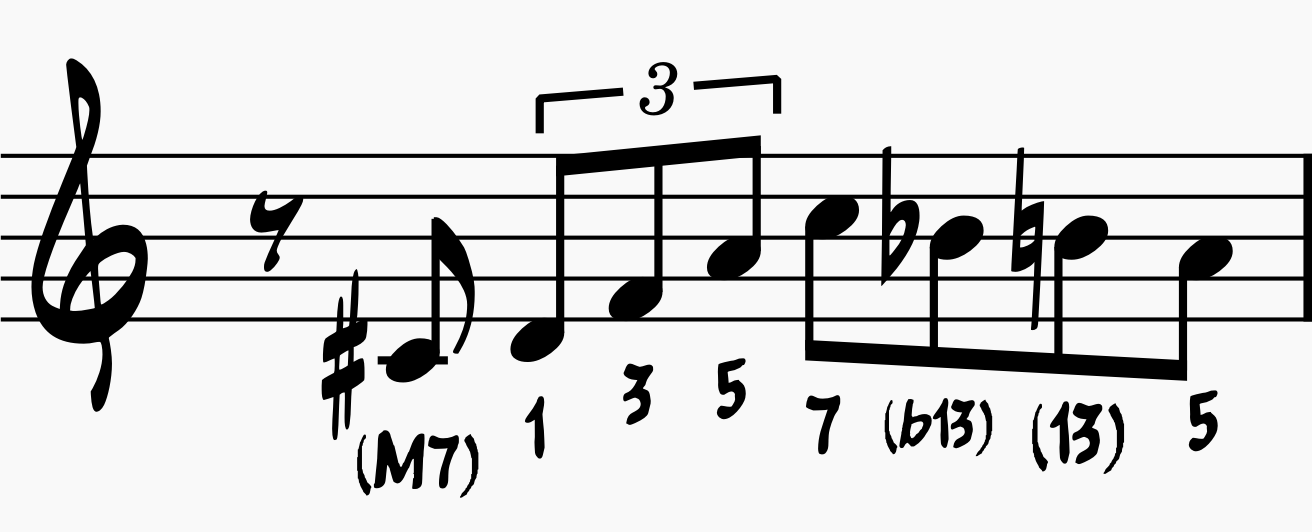

Chromatic Approach Tones

Chromatic approach tones are another very common feature of jazz language. As the name suggests, chromatic approach tones are often used to start a phrase (though they don’t have to be). The chromatic approach tone is often placed on the upbeat, so the target note falls on a strong beat.

Here, the phrase starts on an upbeat and leads chromatically to the root of the D-7 chord.

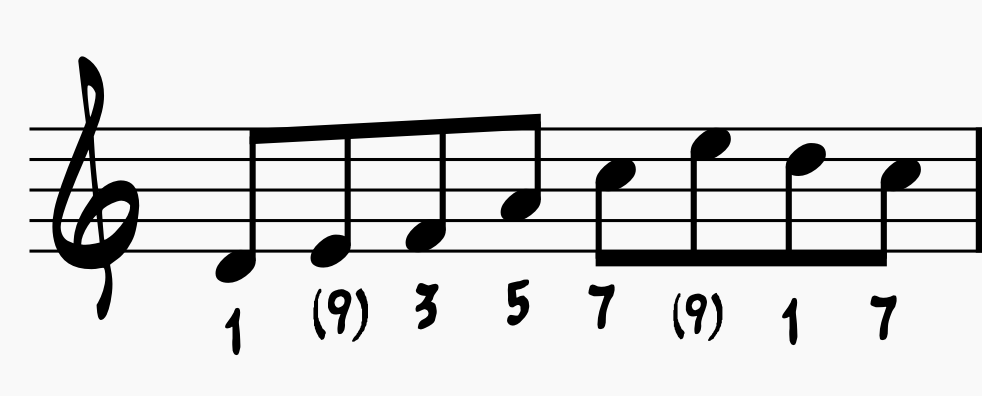

Understanding the Numbers Beneath the Notes

When exploring these licks, you’ll see basic chord tones (1, 3, 5, and 7) given underneath the staff.

You’ll also see notes in parentheses. These represent the chord extensions and alterations that jazz musicians use to create tension or extend the harmony.

What To Expect:

- You’ll see chord tones within the octave: 1, 3, 5, 6, and 7

- And you’ll see chord extensions and alterations in parentheses: (b9), (9), (#9), (11), (#11), (b13), (13)

- You may also see other alterations like (m3), (b5), (#5), or (M7), which indicate alterations within an octave of the root. “M” is used for major, and “m” is used for minor.

Easy ii-V-I and ii-V-I-VI Jazz Licks

Let’s start with a few ii-V-I and ii-V-I-VI jazz licks. We will provide all licks in concert C. However, it’s up to you to take these licks through all keys!

Listen to the audio recordings when learning these licks and see if you can transcribe the lick yourself. Use the notation to check your work.

1. ii-V-I Jazz Lick

This lick uses chord outlines, chromatic passing tones, and enclosures.

2. ii-V-I Jazz Lick

This lick uses chord outlines and chromatic passing tones.

3. ii-V-I Jazz Lick

This lick uses chord outlines.

4. ii-V-I-VI Jazz Lick

This lick uses chromatic passing tones and chord outlines.

5. ii-V-I-VI Jazz Lick

This lick uses chord outlines and chromatic passing tones.

6. ii-V-I-VI Jazz Lick

This lick uses chord outlines and chromatic passing tones.

Jazz Licks Inspired By Jazz Greats

Now that we’ve played a few basic ii-V-I and ii-V-I-VI licks, let’s explore how some of jazz music’s heavy hitters would approach these progressions. The recorded solos of those listed heavily inspired the following licks.

7. ii-V-I Jazz Lick in the Style of Charlie Parker

This lick sounds cool because it imposes an F-7 chord over the G7. This gives you many altered extensions. This lick is also mostly made of chord outlines.

8. ii-V-I Jazz Lick in the Style of Charlie Parker

This lick uses three of the characteristics of jazz language we discussed above: chord outlines, enclosure figures, and Checkchromatic passing tones.

9. iii-VI-ii-V Jazz Lick in the Style of Sonny Rollins

This lick uses chord outlines, chromatic passing pones, and enclosure figures.

BEFORE YOU CONTINUE...

If you struggle to play amazing jazz solos and want to learn the secret strategies the pros are using to improvise, our free guide will get you on the right track.

10. ii-V-I-VI Jazz Lick in the Style of Chet Baker

This lick is an example of classic bebop vocabulary and frequently uses chromatic passing tones.

11. ii-V-I Line in the Style of Kenny Burrell

This lick uses chromatic passing tones, chord outlines, and chromatic approach tones.

12. ii-V-I-vi Jazz Lick in the Style of Miles Davis

This lick uses chord outlines, chromatic approach tones, chromatic passing tones, and enclosure figures!

13. Minor iiø-V-i Jazz Lick in the Style of Miles Davis

This shorter minor iiø-V-i lick uses chromatic passing tones and chord outlines.

14. iiø-V-I Jazz Lick in the Style of Miles Davis (Resolves to Major I)

This crazy lick is full of enclosure figures and chromatic passing tones.

15. Rhythm Changes Lick in the Style of Larry McKenna

This lick is made of mostly chord outlines and also features an enclosure.

16. Lady Bird Turnaround Lick Back to the I. (Giant Steps Lick)

This “Giant Steps” lick can be imposed over turnarounds that lead back to the I. It is made from mostly chord outlines. Check out our article on improvising over Giant Steps changes.

Blues Licks

Now, let’s spend some time on blues licks. The blues is a vital component of jazz; therefore, many players will infuse their licks with motifs characteristic of the blues.

The most characteristic feature of the blues is the fluidity of the 3rd. Blues music is microtonal by nature. The “blue note” is somewhere between a major third and a minor third. So, many players will opt for one or the other (or both) when improvising.

17. Minor Pentatonic Blues Lick in the Style of Kurt Rosenwinkel

This whole lick is basically built from the minor blues scale. For more on the minor blues scale, check out our post on Blues Scales.

18. Jazz-Blues Lick for the Opening Four Bars of the Blues

The last three licks can be glued together to play over a chorus of the blues. Here is the first one:

19. Jazz-Blues Lick for the Next Four Bars of the Blues

20. Jazz-Blues Lick for the Last Four Bars of the Blues

Piecing Blues Licks Together Over a Twelve-Bar Blues Form

You get a full blues solo when you piece together licks 18, 19, and 20! Take this solo through all 12 keys.

Transcribe and Write Your Own Jazz Licks

According to his biography, renowned saxophonist Michael Brecker wrote and practiced one blues solo every day for a year. Among many of his incredible practice routines, that act contributed to his prowess as a jazz improviser.

Composing and improvisation share a special relationship. When we improvise, we are composing on the spot. There is hardly any time to think, plan, or edit when we are in the middle of a solo.

However, by listening to and transcribing the jazz solos of musicians we admire and then composing our own jazz licks and solos, we are strengthening that improvisational neural pathway in our brains.

Composing jazz solos is like improvising outside of time. We can change what doesn’t work and keep what we like. Then, by practicing these composed solos as etudes, we are priming our brains for when it’s our turn to solo on the gig.

If you want to master jazz improvisation, then you should practice writing your own jazz licks! Check out this podcast episode on 9 chord progressions you need to know and write licks over them using the devices we discussed above.

Want To Master Jazz Licks and Become The Best Jazz Player You Can Be? Join the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle!

Ready to blast through practice plateaus that are holding you back from reaching your jazz improvisation and musicianship goals?

The Inner Circle is designed to help players who are struggling to get it all together. We have courses designed to help you play what you hear, create melodic improvisational lines, and understand the theory behind what you are playing.

Want to level up your jazz chops? Join the Inner Circle.