Though it is practically a cliché in the jazz world today, it is nonetheless true to remark that 1959 was a profoundly significant year in jazz history.

In an astonishing creative outpouring, at least five seminal jazz recordings were created and released at the close of the 1950s, all of which suggested intriguing and contrasting potential vectors for the music’s future: Charles Mingus’s Mingus Ah Um, Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, and the bestselling jazz recording of all time, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue.

Ornette Coleman’s groundbreaking 1959 Atlantic Records album The Shape of Jazz to Come has indeed become an iconic part of the jazz canon.

With his third album, Coleman almost single-handedly launched a new stylistic movement in jazz which developed into a sub-genre of jazz sometimes called free jazz or avant-garde jazz.

Though Coleman was and still remains a divisive figure in the jazz world for some, I certainly learned a lot about effective and compelling jazz style and phrasing from listening to his music and transcribing his performance of the melody and his improvisations on his composition “Lonely Woman” from The Shape of Jazz to Come.

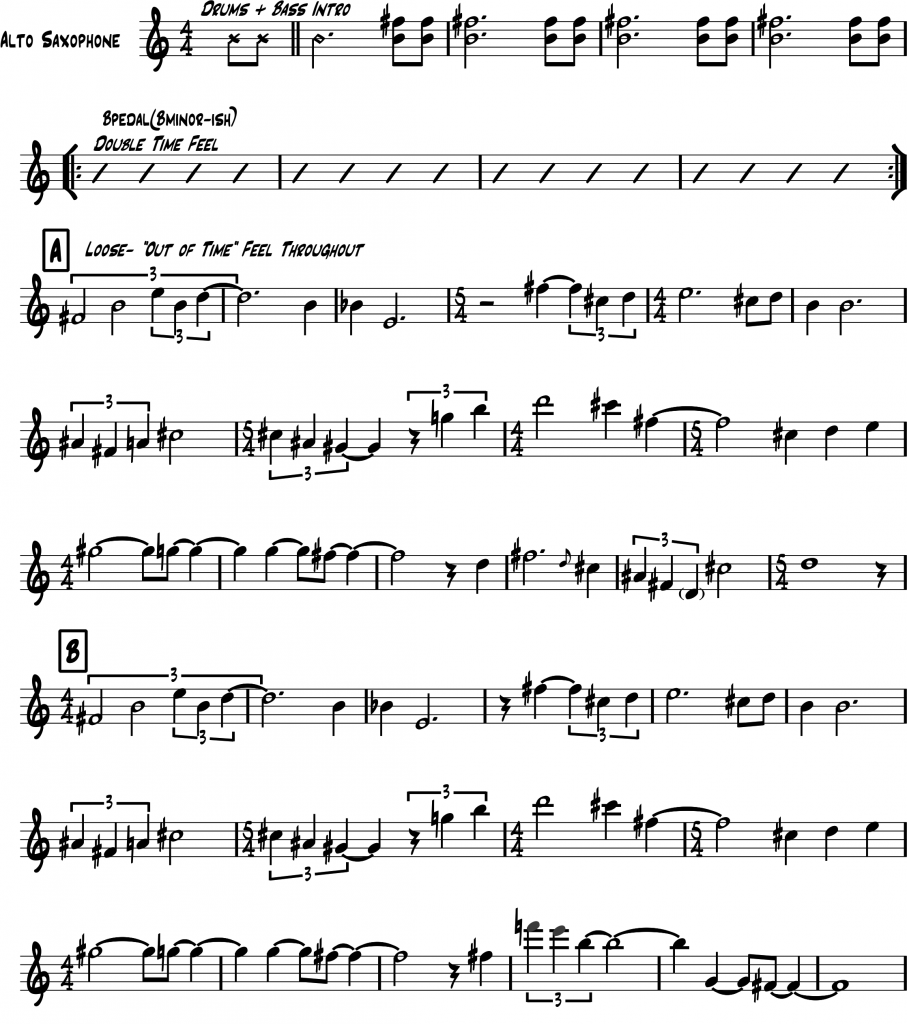

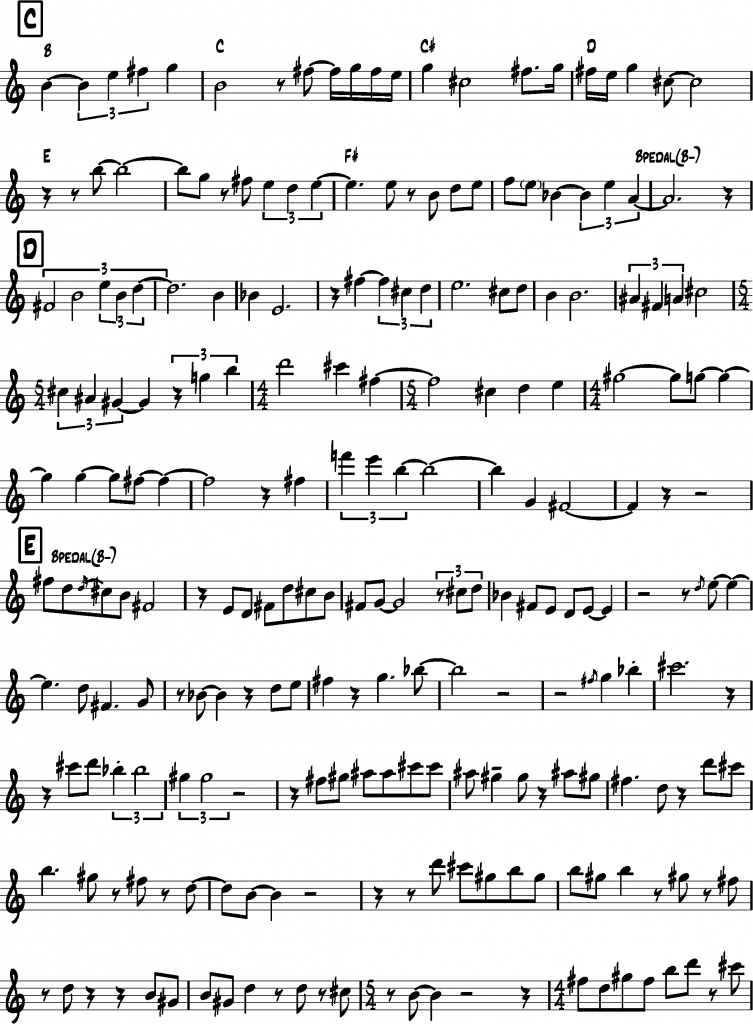

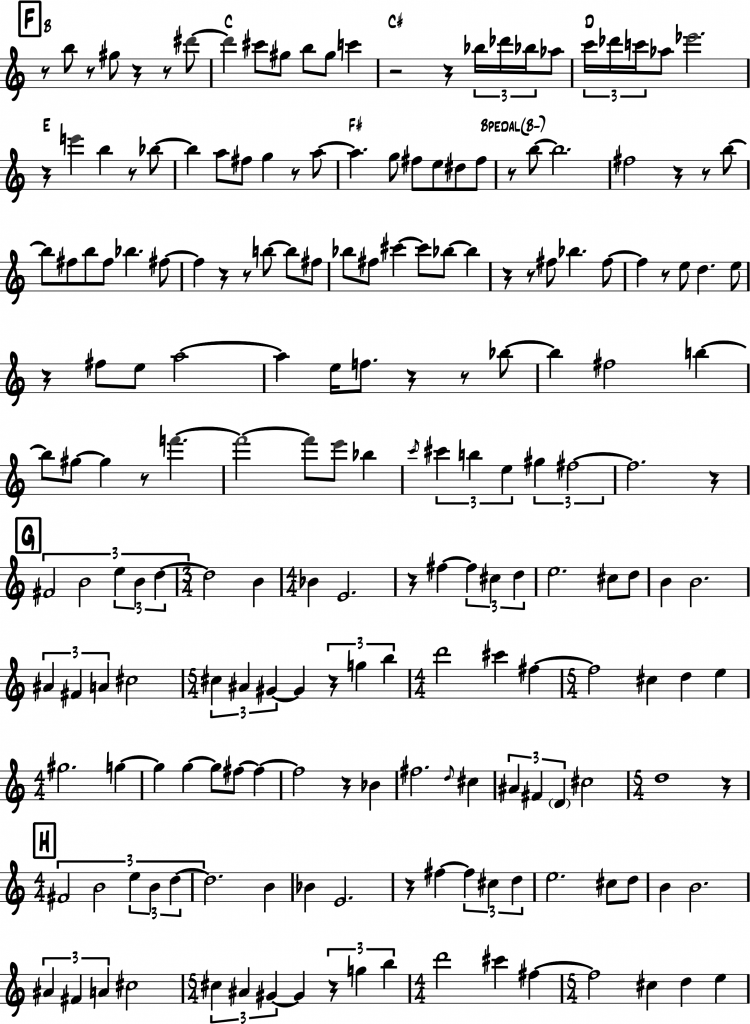

So with this post, I’d like to share my transcription on Coleman’s solo and then give a summary of what I learned from this classic jazz solo.

Please note the transcription was done on alto saxophone and is therefore notated for Eb instruments. Since the piece is basically in D minor, this means it is notated in B minor. Here it is:

There’s so much depth in this solo that I could go on a long rant about it if I’m not careful, so I’ve tried to boil it down to 3 concise takeaways:

1. Simple melodies can have immense amounts of feeling and impact

The melody to “Lonely Woman” and Coleman’s improvised solo are relatively simple, and he generally sticks to B minor (D minor in concert pitch) melodic vocabulary.

He freely mixes B natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor ideas. He never really plays any double time melodies and he avoids any obvious bebop vocabulary, even though he was strongly influenced by Charlie Parker.

His playing is drenched with emotion because he plays with a lot of strong bluesy elements such as bent pitches. He makes simple melodies captivating by milking every note and phrase and saturating his playing with bent notes, scoops, wails, timbral changes, and subtle vibrato.

You can only really understand these elements by following/playing along with the original recording while going through the transcription.

I didn’t even attempt to notate all of the bent notes, scoops, and articulations because there is so much nuance and detail that you can’t really accurately portray Coleman’s phrasing using traditional Western music notation, and the page would be oversaturated and cluttered with notes and notations if I tried anyway.

2. You don’t need to place every phrase right in the rhythmic pocket to make your solo feel good

Unlike many hard-bop players, Coleman doesn’t always play his ideas right in the “pocket” during this solo. He often floats above the groove laid down by the bass and drums.

It is often difficult to tell whether he is feeling/playing quarter note triplets or eighth notes as his primary subdivision of the beat. And yet, for me at least, this recording still truly swings, and I wouldn’t say Coleman has “bad time.”

On the contrary, I think it is tremendously difficult to walk the line between playing triplet and 8th-note subdivisions as deftly as he does. Because he is playing so laid-back and rhythmically loosely, it adds to the sorrowful, bluesy feeling of the piece and gives his playing an ethereal aura.

Plus, it helps that the bass and drums are laying down a groove that feels so solid and good that Coleman truly has the freedom to phrase in a more floaty manner.

3. Good melodic development can keep a listener interested even if the harmony is bare and/or static

Most of the piece is essentially a “time no changes” vamp (which means the music has a steady beat, but no strictly predetermined form or chord changes), and there is no chordal accompaniment since the recording lacks a guitar, piano, or other chordal instrument.

The consequence is that there is a lot of harmonic freedom and space. It can be risky to play in this manner because the performance can feel empty or static without the aid of harmonic progressions propelling the music forward.

However, Coleman maintains the listener’s interest by playing satisfying melodic fragments or ideas that he repeats and subtly varies, all the while sticking close to the spirit and content of the song’s initial melody. It’s a great model to follow as you construct a solo over a vamp, chordless composition, and/or modal song.

A disclaimer about the transcription:

Since “Lonely Woman” doesn’t really have a set form in the traditional jazz sense (i.e., there’s no 32-bar form and even the basic meter/bar lines aren’t always clear), I’ve done my best to try to capture what I think I heard on this recording, but I can’t guarantee everything is absolutely correct.

It shouldn’t matter anyway, because, in my opinion, the notes and rhythms are of secondary importance to trying to truly get a feel for Coleman’s tone, time-feel, use of extended techniques/blue notes, and his sense of phrasing and melodic development.

You can only really understand these elements by following/playing along with the original recording while going through the transcription. I didn’t even attempt to notate all of the bent notes, scoops, and articulations because there is so much nuance and detail that you can’t really accurately portray Coleman’s phrasing using traditional Western music notation, and the page would be oversaturated and cluttered with notes and notations if I tried anyway.

There is so much to learn from this solo, and I encourage you to listen to the recording as you follow along and see what you learn from it for yourself.