In the 1950’s, Miles Davis released a series of iconic recordings of jazz standards with his “first great quintet,” which, in its most classic format, featured Miles on trumpet, John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and “Philly” Joe Jones.

Miles rapidly released a series of classic albums in the 1950’s, since he was eager to fulfill his contractual obligations with the Prestige so that he would be free to start making albums for his new label, Columbia Records.

The 1958 album Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet features the band performing a version of tenor saxophonist and sometime Miles Davis collaborator Sonny Rollins’s rhythm changes composition “Oleo.” John Coltrane’s solo on this famous recording is one of the first solos I ever transcribed.

In this post, I want to share with you a few of his specific melodic ideas from this solo.

I want to try to abstract out general strategies to approaching improvising over rhythm changes based on a few of Coltrane’s phrases that I find particularly compelling. Please note that I left the notated fragments from the transcription in the key Coltrane played it on tenor saxophone (C on tenor, since the piece, is in Bb concert).

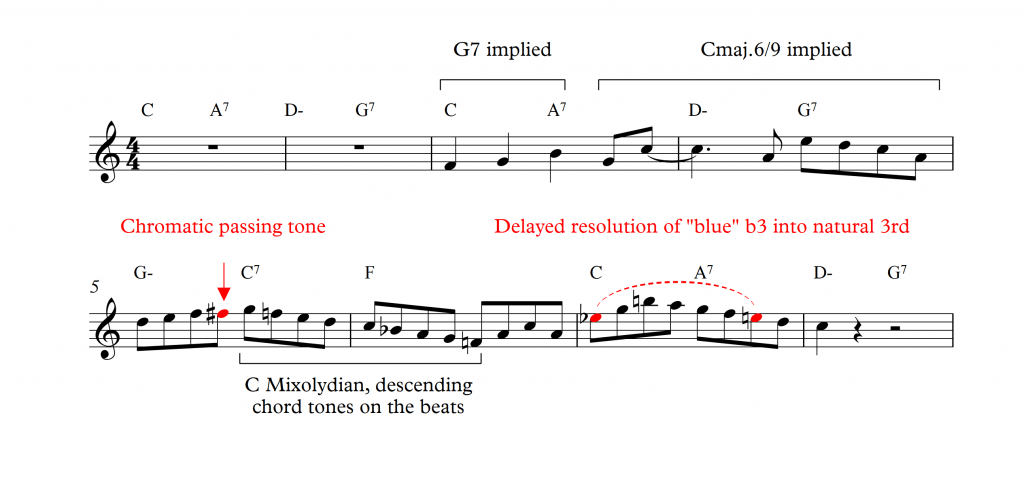

There is so much wonderful information contained in this solo, that all we need to look at is the first 8 measures. There are 3 key things that can help us come with melodic ideas while improvising over rhythm changes.

Here is the track starting right at the beginning of Coltrane’s solo.

Here’s the phrase, followed by my discussion of what I learned from this phrase:

1. You can simplify the harmony to V7-I in the tonic key.

One of the most difficult parts of playing over a rhythm changes, for me at least, has always been handling the speed at which the chords change on the “A” section.

Since it’s the beginning of his solo, Coltrane isn’t in a rush, so he rests for two full measures, and then when he comes in, his first phrase is a strong, simple melodic idea that clearly outlines (using arpeggiated melodies) a V7-I6 (G7 to Cmaj.6) chord progression very clearly.

He is clearly not worried about the underlying harmony here and instead he is just setting up and clearly communicating a simplified chord progression to establish the key of the tune right from the very start of his solo.

2. You can combine bebop scales and diatonic scales to get chord tones on the downbeats.

(Which helps communicate the harmony clearly).

In measures 5–6 of his solo, he plays an ascending scale fragment with a chromatic passing tone (he might have had the G7 bebop scale in his ears of his mind while he played this line).

If you want to learn more about bebop scales, check out this post.

This allows him to land on a chord tone (G, the 5th of C7) on beat 3, and then he sticks to a diatonic C7 scale as he reverses his melodic direction and plays a descending V7-I in the key of the IV (since he’s trying to get to the IV chord in bar 6).

Notice that he doesn’t use any passing tones as he plays the descending scale, because, since he started the scale on beat 3, he doesn’t need any passing tones to get the chord tones to line up on the beats for the C7 and Fmaj. chords.

3. You don’t always have to hit chord tones on the downbeats.

(And non-chord tones can have delayed resolutions for dramatic effect).

In bar 7, Coltrane hits an Eb on the downbeat of the Cmaj. Chord. Superficially, this seems like a “wrong note.” Of course, in general, when playing jazz you can often get away with playing a b3 on a major chord if it is part of a very strong blues-sounding idea or if you resolve it into a major 3rd, which also often gives the melody a bluesy quality.

However, he clearly meant to play it, as it is part of a melodic line in which he is essentially playing a blues Eb to E natural melody, and he merely delays the resolution of the Eb into the E until beat 4 by adding notes in between. This is a really cool melodic technique that can allow you to add elements of surprise and suspense to your melodic lines.

I recommend you memorize this 8-measure phrase, play it along with the recording, and then practice it in all twelve keys. Then, start to vary the melodies within the phrase by rhythmically displacing them, changing a few notes here and there, or adding/subtracting notes. If you can master this task, you’ll have some great melodic templates and general strategic ideas to help you expand your melodic possibilities while improvising over rhythm changes.