Modal interchange is a compositional device that takes basic diatonic chord progressions and pushes them to the next level. If you’ve ever had your face melted by a chord progression but didn’t know exactly what was happening, there’s a good chance you heard modal interchange in action!

This article will explore modal interchange and how it works.

We’ll define modal interchange, explore what it is (and what it isn’t), and examine plenty of examples so that you have a good grasp of the concept by the end of the article! But before we dive in…

If you want to improve your jazz theory skills, check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle. The Inner Circle has everything you need to take your jazz theory knowledge and musicianship skills to the next level.

If you are tired of practice plateaus and musical stagnation, check us out! We’ll help you improve in 30 days or less! Come see what the Inner Circle has to offer.

Table of Contents

What is Modal Interchange or Borrowed Chords?

Modal interchange is a simple concept at heart—even though it leads to some crazy-sounding chord progressions.

Essentially, when you borrow chords from a parallel tonality, mode, or scale taken from the same root, you are using modal interchange chords in your chord progression.

Composers most often choose chords from the parallel minor scale. However, you can choose from any scale or mode so long as it is built from the same root. You can even mix different modes together in a process called modal mixture.

Before exploring all the different scale and mode options available, let’s briefly discuss what modal interchange isn’t. Other compositional devices could be confused for modal interchange, and we want to clear the air and keep you on track!

Modal Interchange is Not a Key Change

The idea behind modal interchange is to incorporate color, variety, and tension into our chord progressions without establishing a new tonal center. A key change—as the name suggests—means a change in the tonal center.

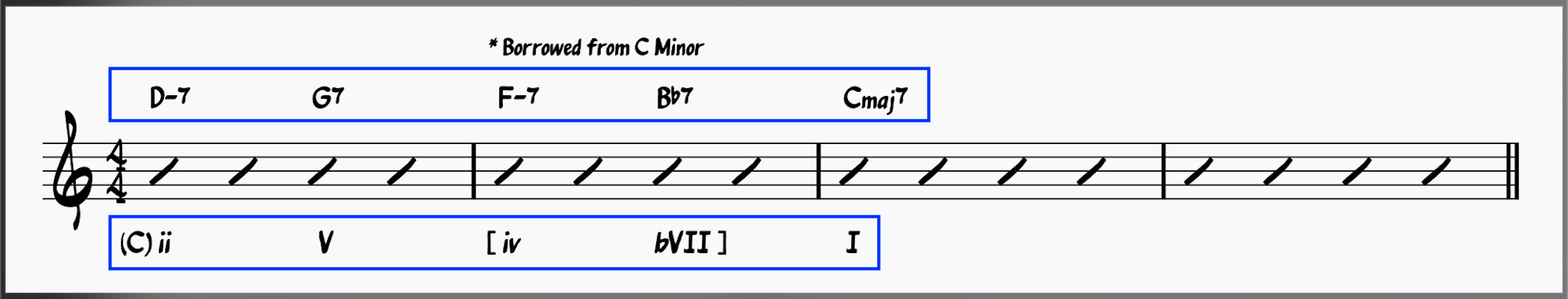

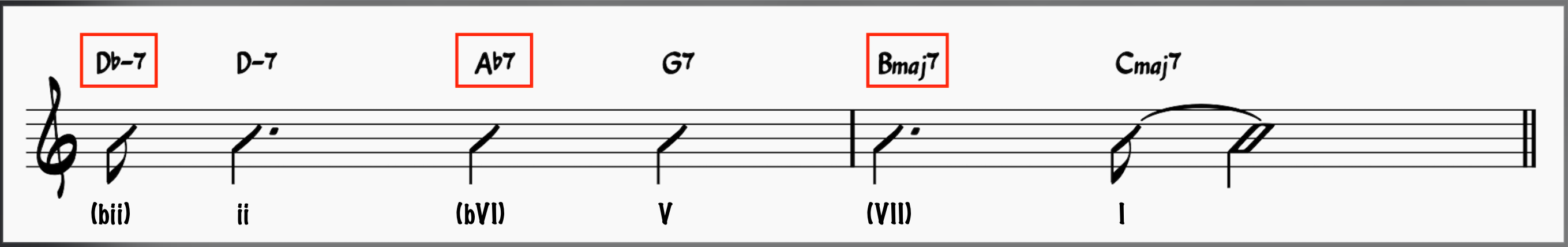

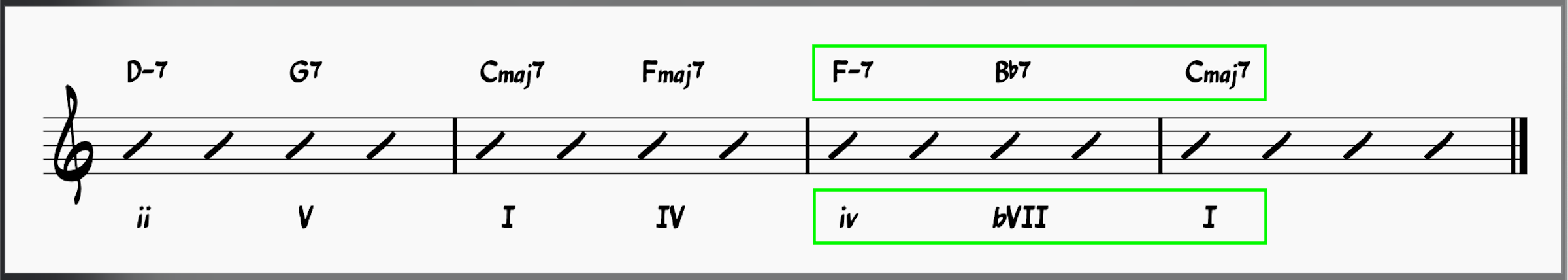

Modal interchange maintains the same tonal center and doesn’t modulate into a new one. For example, below are two chord progressions. One utilizes modal interchange and stays in C, while the other modulates to a new tonal center despite using the same chords.

Modal Interchange:

This example shows modal interchange because the brief ii-V, pulled from the parallel key of C minor, resolves back to C major. Our tonal center didn’t change. We used modal interchange chords to add variety and color to the progression and borrowed them from C minor.

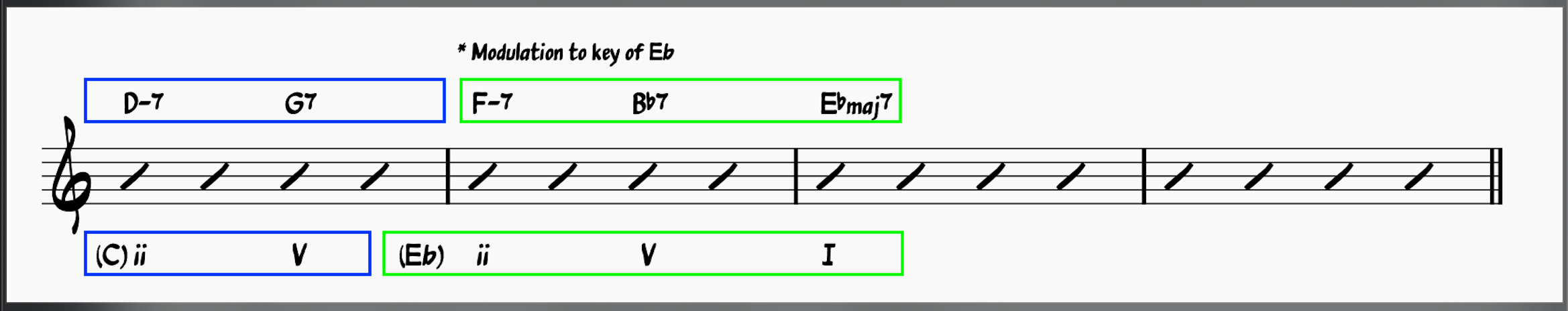

Modulation:

This example is a true modulation because the ii-V in green resolves to a new tonal center—the key of Eb. Though the F-7 and Bb7 chords are the same in both progressions, each progression’s resolution reveals their different functions.

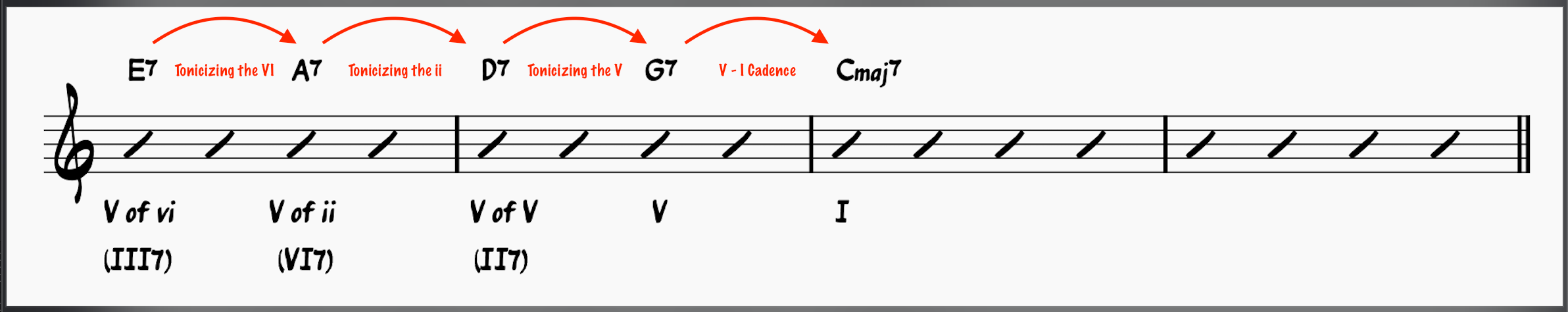

Modal Interchange is Not Tonicization (Secondary Dominants)

As we’ve established, modal interchange does not imply a change in tonal center. Therefore, secondary dominants, which briefly tonicize a chord other than the tonic chord, are not an example of modal interchange.

- Secondary Dominant: A dominant chord that temporarily tonicizes a non-tonic diatonic chord in a chord progression.

Secondary dominants are often used in turnarounds to make the transition back to the tonic chord smoother through the tonicization of each chord in the turnaround progression.

Though any of the dominant chords above could be defined as a “borrowed chord” (as in, we can find a parallel mode for each chord), the function of a secondary dominant differs from the function of modal interchange. In sum:

- Secondary Dominants briefly tonicize a non-tonic chord in a diatonic chord progression.

- Modal Interchange chords pull from parallel scales and modes to add color and variety to a chord progression.

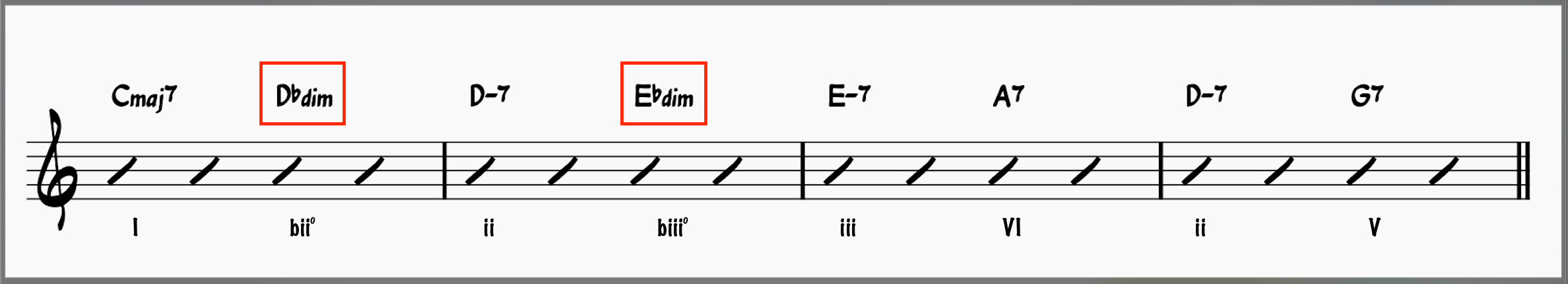

Modal Interchange Chords Are Not the Same Thing as Passing Chords or Chromatic Approach Chords

Passing chords are inserted between two diatonic chords in a chord progression to create a smooth and coherent voice leading between those two chords.

These chords can be of any quality, though they are usually diminished, dominant, or parallel to the starting or resolving chord. Here is an example of diminished passing chords in action:

Though you can certainly use a bii° as a modal interchange chord, whether it is a modal interchange chord or just a passing chord depends on its intent.

Remember, the idea behind modal interchange chords is to introduce harmony from other modes or scales from the same tonal center into the main progression. A passing chord aims to connect two diatonic chords with a fleeting intermediary chord.

Similarly, chromatic approach chords resolve up or down a half step to the target chord. These types of chords are often the same quality as the target chord. They are frequently used as embellishments of the main progression, not bonafide parts of it.

Ab dominant is the VI chord in the C Locrian mode, so it could be used as a modal interchange chord; however, in the example above, it is clearly a temporary chromatic approach chord with G7 as the target chord.

Modal Interchange Offers Composers Many (Many) Options

Now that we know what modal interchange is and isn’t, let’s explore all the chord options we have available to us!

First, we’ll establish all the regular old diatonic chords, then we’ll go through the modes from the same tonic. After that, we’ll look at non-diatonic scales like the melodic and harmonic minor scales.

Diatonic Chords

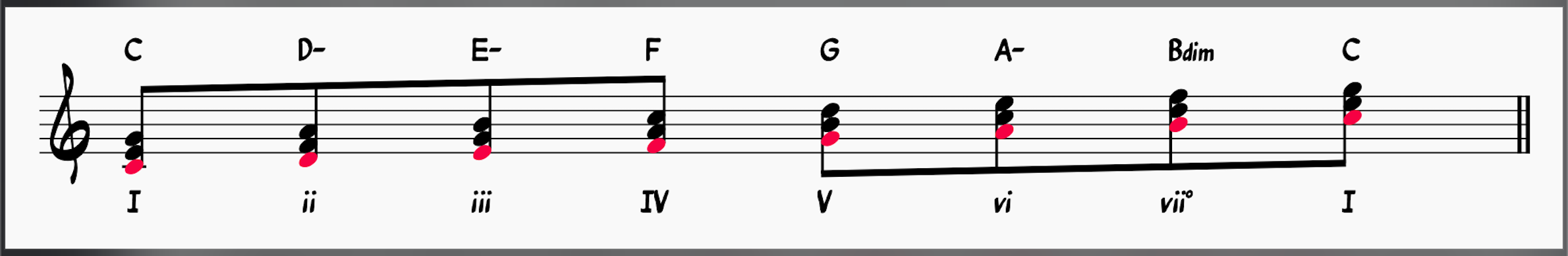

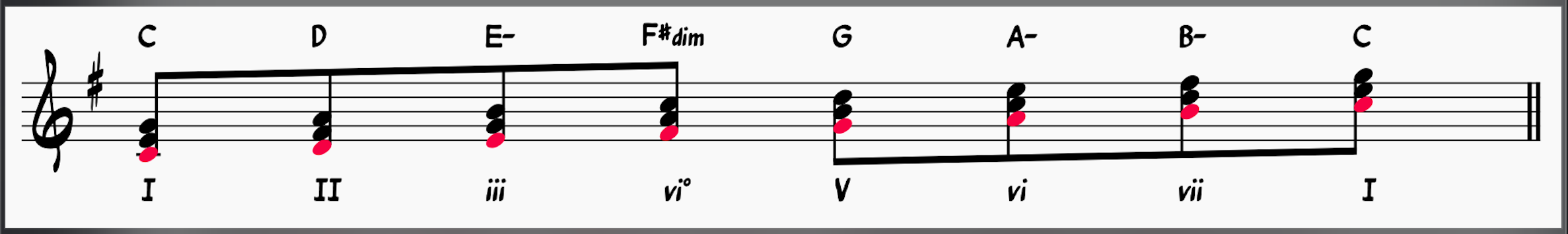

To truly grasp how modal interchange works, we need to set up our foundation (and diatonic chords are one of the foundational elements of music theory). In essence, diatonic chords are the chords you get when you harmonize the scale degrees of the major scale.

Here’s how that works:

When you harmonize the major scale notes, you get all the diatonic chords in a major key. In the example above, we harmonized the C major scale and ended up with seven chords:

- vii°: B diminished

- vi: A minor

- V: G major

- IV: F major

- iii: E minor

- ii: D minor

- I: C major

Modes of the Major Scale

The following section will go through each mode from C and examine all the chords in each mode. Some of the chord options we’ll go over are redundant.

For example, a Bb major chord can be borrowed from C Dorian, C Mixolydian, and C Aeolian. When temporarily borrowing chords like Bb, you could be implying any of these modes, which would still be an example of modal interchange.

So, the purpose of going through all the modes from C is to establish all the possibilities, despite the redundancies. With that out of the way, let’s dive in!

Chords in C Dorian (Bb)

C Dorian is the second mode of Bb major.

- C – D – Eb – F – G – A – Bb – C

When we harmonize the C Dorian scale, we get the following chords:

- VII: Bb major

- vi°: A diminished

- v: G minor

- IV: F major

- III: Eb major

- ii: D minor

- i: C minor

For more on the Dorian scale, check out our guide to Dorian minor on piano and guitar.

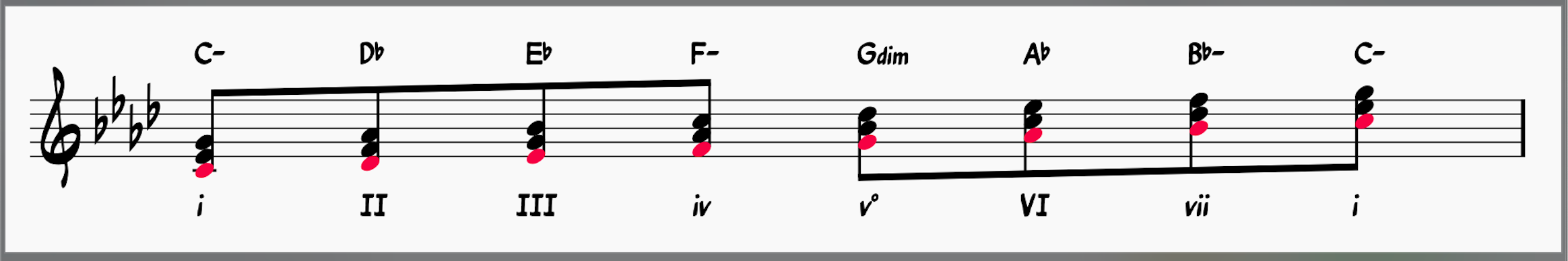

Chords in C Phrygian (Ab)

C Phrygian is the third mode of Ab major.

- C – Db – Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C

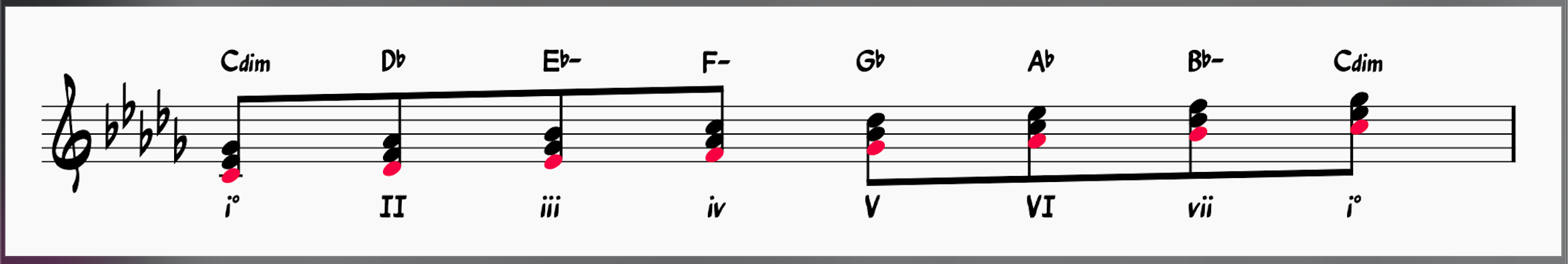

When we harmonize the C Phrygian scale, we get the following chords:

- vii: Bb minor

- VI: Ab major

- v°: G diminished

- iv: F minor

- III: Eb major

- II: Db major

- i: C minor

Chords in C Lydian (G)

C Lydian is the fourth mode of G major.

- C – D – E – F# – G – A – B – C

- vii: B minor

- vi: A minor

- V: G major

- iv°: F diminished

- iii: E minor

- II: D major

- I: C major

For more on the Lydian mode, check out our guide to the Lydian scale on guitar and piano.

BEFORE YOU CONTINUE...

If music theory has always seemed confusing to you and you wish someone would make it feel simple, our free guide will help you unlock jazz theory secrets.

Chords in C Mixolydian (F)

C Mixolydian is the fifth mode of F major.

- C – D – E – F – G – A – Bb – C

- VII: Bb major

- vi: A minor

- v: G minor

- IV: F major

- iii°: E diminished

- ii: D minor

- I: C major

For more on the Mixolydian mode, check out our article on the Mixolydian scale on piano and guitar.

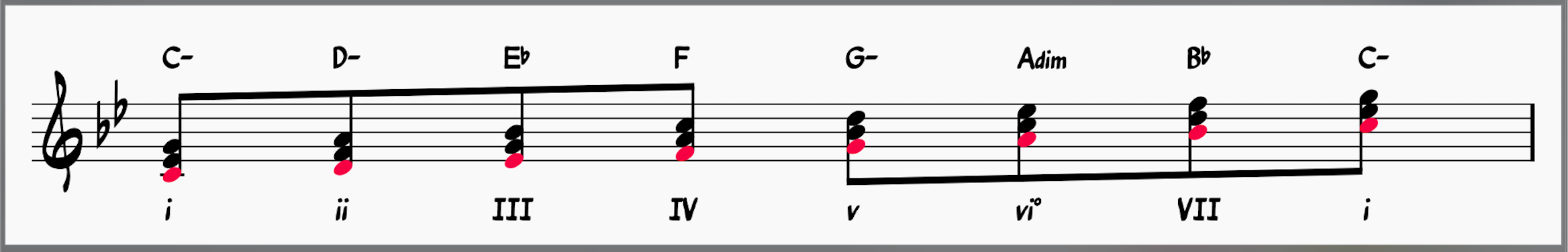

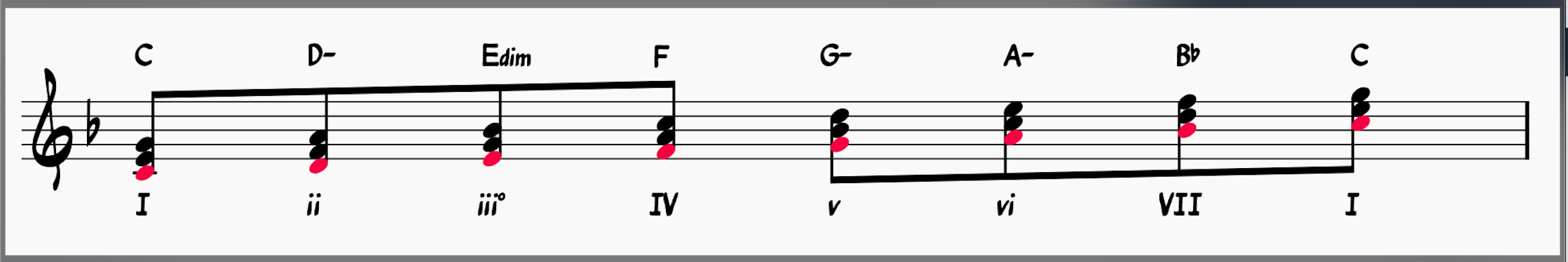

Chords in C Aeolian (Eb)

The C Aeolian mode is the sixth mode of Eb major.

- C – D – Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C

- VII: Bb major

- VI: Ab major

- v: G minor

- iv: F minor

- III: Eb major

- ii°: D diminished

- i: C minor

Check out our article on the Aeolian mode on piano and guitar for more information.

Chords in C Locrian (Db)

C Locrian is the seventh mode of Db major.

- C – Db – Eb – F – Gb – Ab – Bb – C

- vii: Bb minor

- VI: Ab major

- V: Gb major

- iv: F minor

- iii: Eb minor

- II: Db major

- i°: C diminished

For more on the modes of the major scale, check out our ultimate guide to musical modes.

In addition to the major scale modes, we can borrow chords from non-diatonic scales like the harmonic minor scale and the melodic minor scale.

Let’s explore the chords in C harmonic minor and C melodic minor.

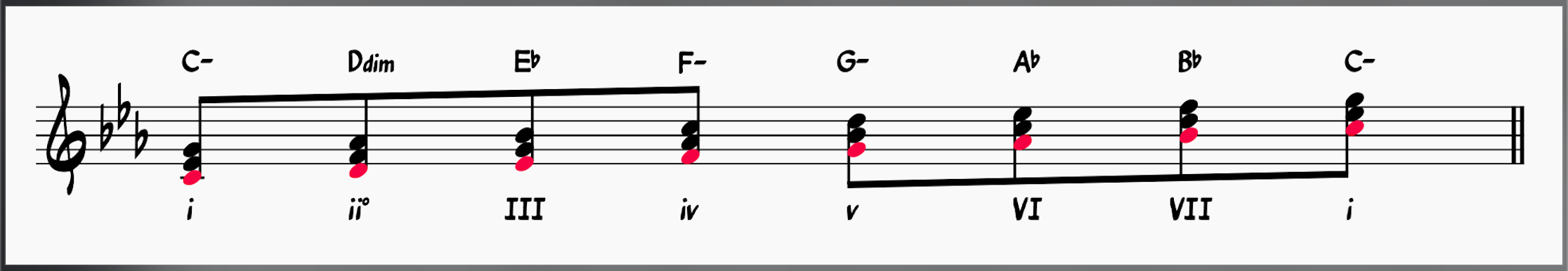

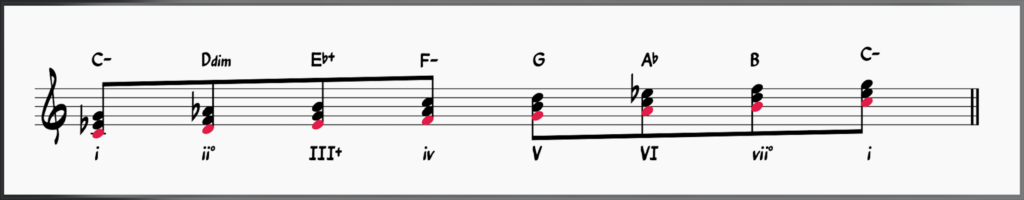

Harmonic Minor Scale

The C harmonic minor scale is a C minor scale with a major seventh interval instead of a minor seventh.

This scale is unique because it has a minor third gap between the sixth and seventh intervals. When harmonized, we get an augmented triad on the third scale degree, which is not found in the major scale.

- C – D – Eb – F – G – Ab – B – C

- vii°: Bb dim

- VI: Ab major

- V: G major

- iv: F minor

- III+: Eb augmented

- ii°: D diminished

- i: C minor

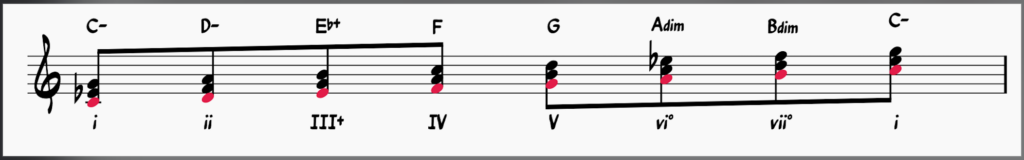

Melodic Minor Scale

The C melodic minor scale is a C minor scale with a major sixth and a major seventh. In classical music, these raised sixth and seventh intervals are only played when ascending and are lowered when descending.

- C – D – Eb – F – G – A – B – C

- vii°: Bb dim

- vi°: A dim

- V: G major

- IV: F major

- III+: Eb augmented

- ii: D minor

- i: C minor

Symmetrical Scales

You can also borrow chords from symmetrical scales, such as the diminished scale and the whole tone scale, though these chords are respectively diminished and augmented.

For more on diminished scales, check out our article on diminished scales.

Modal Interchange Chords in Action

Let’s briefly explore one of the most common ways to use borrowed chords in jazz!

Backdoor Progressions

The backdoor progression is a staple of jazz harmony. It is also a great example of modal interchange, with the borrowed chords coming from the parallel minor.

This progression is called a “backdoor” progression because it is an alternative to the “front door” or more standard ii-V-I progression. Instead of ii-V-I, you’d play an iv-bVII7-I:

Tunes That Use the Backdoor Progression:

Stella By Starlight

How Deep is the Ocean

I Should Care

I’ll Be Seeing You

Misty

Groovin’ High

Dolphin Dance

Just Friends

Want to Master Advanced Music Theory Concepts Like Modal Interchange? Join the Inner Circle!

If you want to learn more about jazz theory and take your jazz chops to the next level, check out the Learn Jazz Standards Inner Circle. Not only do we learn a new jazz standard each month, but we have over ten years of resources designed to help you take your jazz playing to the next level.

Improve in 30 days or less. Join the Inner Circle.